Jake Sullivan’s Rome meeting with Chinese counterpart left US officials pessimistic about steering Beijing away from backing Moscow

China has already decided to provide Russia with economic and financial support during its war on Ukraine and is contemplating sending military supplies such as armed drones, US officials fear.

The US national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, laid out the US case against Russia’s invasion in an “intense” seven-hour meeting in Rome with his Chinese counterpart, Yang Jiechi, pointing out that Moscow had feigned interest in diplomacy while preparing for invasion, and also that the Russian military was clearly showing signs of frailty.

The US delegation in Rome had not expected the Chinese diplomats to negotiate, seeing them as message deliverers to Beijing.

“It was an intense seven-hour session, reflecting the gravity of the moment, as well as our commitment to maintaining open lines of communication,” a senior administration official said. “This meeting was not about negotiating specific issues or outcomes, but about a candid, direct exchange of views.”

Asked if it had been successful, the official replied: “I suppose it depends on how you define success, but we believe that it is important to keep open lines of communication between the United States and China, especially on areas where we disagree.”

However, the Americans walked away from the Rome meeting pessimistic that the Chinese government would change its minds about backing Moscow.

“The key here is first to get China to recalculate and re-evaluate their position. We see no sign of that re-evaluation,” said another US official familiar with the discussions. “They’ve already decided that they’re going to provide economic and financial support, and they underscored that today. The question really is whether they will go further.”

Top of the Russian military shopping list in China are armed drones and various forms of ammunition, but any military transfers would not be straightforward.

“Both sides understand that they don’t share common systems, and so that makes it problematic,” the official said. CNN reported that the Russian military is also asking for ration packs, underlining its severe logistical problems in a more prolonged and tougher conflict than it anticipated.

Russia needs economic and financial aid most urgently, in the face of devastating sanctions imposed by the US and its allies since the 24 February invasion. The country is danger of default on its debt payments, with two interest payments due on Wednesday, though it will have a 30-day grace period.

Moscow is unable to access nearly all of its $640bn in gold and foreign exchange reserves, but still holds part of those reserves in yuan, so Beijing will be able to step in to provide immediate assistance.

There is pessimism in Washington about the possibility of steering China away from throwing in its lot with Russia, largely because it sees the partnership as being driven from the top.

“It really is a project of Xi Jinping. He is totally, fundamentally behind this closer partnership with Russia,” the US official said. There is more scepticism lower down the ranks, but Xi and Putin have bonded over their shared view of the US as being heavy- and high-handed, and determined to end the period of US global dominance.

If China does back Russia in its showdown with the west, the Biden administration will shift its focus to persuading allies, in Europe particularly, to rethink their relationships with Beijing. Sullivan is due in Paris on Tuesday for discussions with the French government.

“The United States believes that the key here is a careful process of dialogue and discussion with Europe about what China is revealing about its global policies and priorities,” the US official said. “Our goal basically is to carefully engage China, letting the Europeans know [what we are doing] all along, but if it becomes clear that [China] is moving in another direction, so be it.”

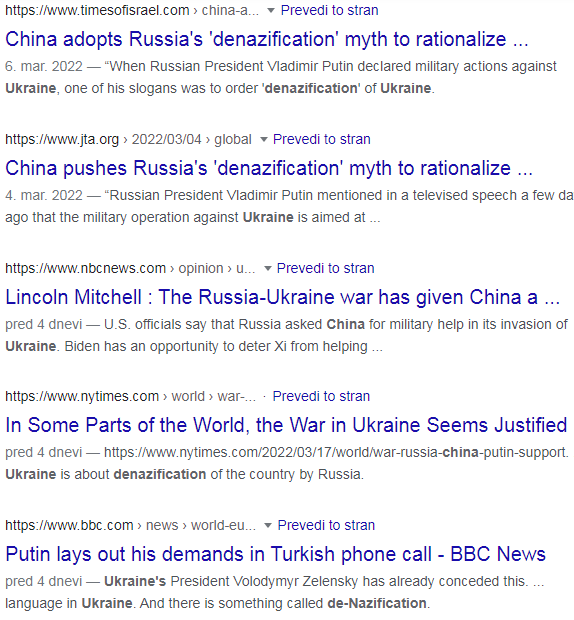

China pushes Russia’s ‘denazification’ myth to rationalize Ukraine invasion

TAIPEI (JTA) — Many countries have roundly rejected Russian President Vladimir Putin’s argument that his attack on Ukraine is needed to achieve the “denazification” of that country. But the argument is alive and well in Chinese state-run media.

“Russian President Vladimir Putin mentioned in a televised speech a few days ago that the military operation against Ukraine is aimed at protecting the people who have suffered abuse and genocide by the Kyiv regime for eight years. For this reason, Russia will seek to demilitarize and de-Nazify Ukraine,” one article on the state-backed site Wen Wei Po read.

China is in an awkward position as Russia wages its war in Ukraine: Beijing has interests in both Russia and with the West, so it has refrained from antagonizing Putin while also not openly supporting him. The New York Times reported that, behind the scenes, Chinese officials had asked Putin to delay his planned invasion until after the Beijing Olympics. Publicly, Chinese officials have said that China respects Ukraine’s territorial integrity.

This week, China was one of 35 countries to abstain from a United Nations vote to condemn Russia — placing it well outside the mainstream, but also not in the tiny minority of nations to side with Russia and oppose the resolution.

Chinese media offers another clue about where the government stands on the war Putin started, and on his reasons for starting it. (Chinese news media is subject to heavy government censorship and can be understood as reflecting the official state position.)

Official Chinese news sites have published baseless claims in recent articles claiming that the United States trained Ukrainian neo-Nazis to destabilize Hong Kong during protests there in 2019.

“When Russian President Vladimir Putin declared military actions against Ukraine, one of his slogans was to order ‘denazification’ of Ukraine. Soon after, in China’s cyberspace, Putin’s remarks invoked the memories of many Chinese citizens,” the state-backed site Taihai Net wrote in a Feb. 28 story.

Chinese social media users have also used Russian talking points about Nazis, according to a New York Times report that said many users are “bringing up the Azov Battalion as if it represented all of Ukraine.” The ultranationalist paramilitary group has a reputation for including neo-Nazis and participating in antisemitic displays. But it numbers at most several hundred in an army of about a quarter million.

Overall, the discourse seeks to rationalize the Chinese state’s behavior in Hong Kong, widely perceived internationally as an assault on democracy, while simultaneously attacking the United States, according to an analysis by the Taiwan-based Information Operations Research Group, an organization that researches Chinese influence and media manipulation in Taiwan.

In 2019, Hong Kongers began protesting an extradition law that most saw as an overreach of China’s power into the region. The bill was eventually scrapped, but a 2020 national security law has since led to arrests of activists, closures of independent news outlets and a mass exodus from the region.

This is not the first time that Ukraine and Nazism have entered the political discourse in China. Last year, state-backed news organizations criticized the United States and Ukraine after the two countries voted against a United Nations resolution aimed at “combating glorification of Nazism, neo-Nazism and other practices.”

At the time, the United States argued that the resolution represented “thinly veiled attempts to legitimize Russian disinformation campaigns denigrating neighboring nations and promoting the distorted Soviet narrative of much of contemporary European history, using the cynical guise of halting Nazi glorification.”

That disinformation campaign has kicked into high gear in recent weeks, with Putin saying repeatedly that Ukraine is run by neo-Nazis and has an army filled with them.

Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, is Jewish and lost family members to the Holocaust. “How could I be a Nazi?” he asked in an appeal to Russians on the eve of the war.

Invocation of the Holocaust in political propaganda isn’t new for China. State media has criticized other countries such as Lithuania — whose relationship with China has cooled since last year — by pointing to historical antisemitism and the Holocaust. The Chinese state has also compared 2019 protests in Hong Kong to the Holocaust and claimed responsibility for saving Jewish refugees in Shanghai during World War II. While the city did provide refuge to tens of thousands of Jewish refugees from Europe, it was at the time governed by several powers. The People’s Republic of China was not founded until 1949.

No comments:

Post a Comment