- Today we are faced with the question whether the terrible sacrifices that have been made can be a closed page of history? I answer this question: no. They cannot, because history and those cards written down by the Germans have a specific dimension. (...) The descendants of destroyers and criminals, today's Germany, must realize that without actual redress, there can be no question of closing this page of history. Any justice, the truth about that time, the restoration of the common good and reconciliation must be combined with elementary justice, and this in turn with the settlement of those cruel crimes, the prime minister pointed out. - We must not forget the unsettled crimes - he added.

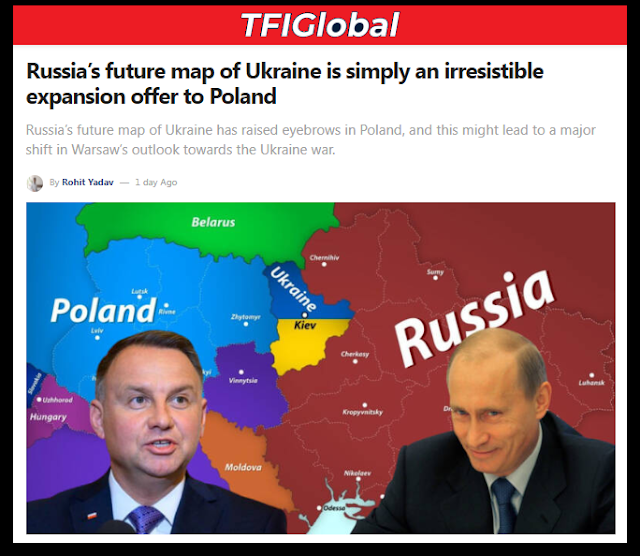

HOW POLAND WANTS HER CHUNK OF UKRAINE ARE NOW 100% VALID. Question further opens in respect to my pointing finger in the past toward Kaczynski's pro Russo Polish politics about just how far I was from being 100% correct on topic as crises(tensions based on which we will know defacto whether those were/are fake or real - I do not exclude possibility of Kaczzynski doing his best to distort my views for me to cause myself as much damage as possible or/and Russians brainwashing me on the side with Kaczynski's doppelgangers) apparently developed between Poland and Russia ran Belarus state. Time certainly is the best judge. Opening old wounds during Russian war on Ukraine in respect to WW2 is as primitive as anything can be, but Duda dignified(prided) himself with, "and I will help him"(as if none in Poland and Ukraine exist, but Zelensky and Duda)....

Poland asks Ukraine to confront dark past despite common front against Moscow

WARSAW (Reuters) - Poland's president on Monday called for Ukraine to admit what he called the shameful truth about how Ukrainian nationalists had massacred over 100,000 Poles during World War Two, despite Kyiv and Warsaw's common front against Russia now.

The remarks by Andrzej Duda were made on the 79th anniversary of the 1943 killings in Volhynia in Nazi-occupied Poland and were a pointed reminder of the complex historical ties between Warsaw and Kyiv at a time when Russia's invasion of Ukraine has brought the two neighbours closer together.

Poland has opened its doors to Ukrainian refugees and Duda has allowed his country to be used as a logistics hub to keep Ukraine supplied as it fights an exhausting war of attrition against Russia.

But at a Warsaw ceremony on Monday, Duda said that the truth about the wartime massacres and others like it in Eastern Galicia from 1944-45 had to be “firmly and clearly stated” regardless and called on Kyiv to acknowledge the ethnic cleansing of Poles by Ukrainian nationalist militias.

“It was not about and is not about revenge, about any retaliation. There is no better proof of this than the time we have now,” Duda said, referring to the two countries' current cooperation against Russia.

The issue was complex for Ukrainians, he said, since some regarded the same militias as heroes for the resistance they mounted against the Soviet Union and as symbols of Kyiv's painful struggle for independence from Moscow.

"Those who we know were murderers were also heroes for Ukraine, at other times and with a different enemy, and often died at the hands of the Soviets, fighting with deep faith for an independent, free Ukraine," said Duda.

There was no immediate reaction from Ukraine to Duda's comments, but his remarks are likely to be seen as ill-timed in some Ukrainian circles who view attempts to discuss such events now as part of a Russian-inspired attempt to falsely cast Ukraine as a country in need of de-Nazifying, one of the stated aims of what Russia calls its special military operation.

The Polish parliament has said that the murders, carried out between 1943 and 1945 by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists under the leadership of Stepan Bandera, bore elements of genocide.

Ukraine has not accepted that assertion and often refers to the Volhynia events as part of a conflict between Poland and Ukraine which affected both nations.

Polish historians say that up to 12,000 Ukrainians were also killed in Polish retaliatory operations.

(Reporting by Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska; Editing by Andrew Osborn and Jonathan Oatis)

Stepan Bandera

Stepan Bandera | |

|---|---|

Степан Бандера | |

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Stepan Andriyovych Bandera 1 January 1909 Staryi Uhryniv, Galicia, Austria-Hungary (now Ukraine) |

| Died | 15 October 1959 (aged 50) Munich, West Germany |

| Cause of death | Extrajudicially executed by the KGB |

| Citizenship |

|

| Nationality | Ukrainian |

| Spouse(s) | Yaroslava Bandera |

| Relations | Vasyl Bandera (brother) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | Lviv Polytechnic |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Awards | Hero of Ukraine (annulled) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera (Ukrainian: Степа́н Андрі́йович Банде́ра, romanized: Stepán Andríyovyč Bandéra, IPA: [steˈpɑn ɐnˈd⁽ʲ⁾r⁽ʲ⁾ijoʋɪt͡ʃ bɐnˈdɛrɐ]; Polish: Stepan Andrijowycz Bandera; 1 January 1909 – 15 October 1959) was an Ukrainian nationalist leader, politician and theorist of the militant wing (OUN-B), served as head of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists,[1][2] organization responsible for massacres and ethnic cleansings, also implicated in collaboration with Nazi Germany.[1][3]

Born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in the economically backward Galicia (officially Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, created after the first partition of Poland) into the family of a priest of Eastern Catholic Church.[4] After the Empire disintegrated in the wake of World War I, Galicia briefly became a West Ukrainian People's Republic; following the Polish–Ukrainian War of 1918–1919, it was again integrated into eastern Poland. In this period, Bandera became radicalized. He enrolled at the Lviv Polytechnic, where he organized Ukrainian nationalist organizations. For orchestrating the 1934 assassination of Poland's Minister of the Interior Bronisław Pieracki, Bandera was sentenced to death but the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. In September 1939, as a result of the invasion of Poland, he was freed from Bereza Kartuska prison, and moved to Kraków, in the German-occupied zone, where he maintained close connections with Abwehr and Wehrmacht.[5][6]

For a time, Bandera collaborated with Nazi Germany. When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, he prepared the 30 June 1941 Proclamation of Ukrainian statehood in Lviv, pledging to work with Nazi Germany.[7][5] For his refusal to rescind the decree, Bandera was arrested by the Gestapo and on 5 July 1941 held under house arrest.[8] After January 1942 Bandera was transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp but kept in special, comparatively comfortable detention.[9][10][11] In 1944, with Germany rapidly losing ground in the war in the face of the advancing Allied armies, Bandera was released in the hope that he would be instrumental in deterring the advancing Soviet forces. He set up the headquarters of the re-established Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council, which worked underground. After the war, Bandera with his family settled in West Germany where he remained the leader of the OUN-B and worked with several anti-communist organizations such as the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations[12] as well as with the US and British intelligence agencies.[12][4] Fourteen years after the end of the war, Bandera was assassinated in 1959 by KGB agents in Munich, West Germany.[13][14]

On 22 January 2010, the President of Ukraine Viktor Yushchenko awarded Bandera the posthumous title of Hero of Ukraine.[15] The European Parliament condemned the award, as did Russia, Poland and Jewish politicians and organizations.[16][17][18][19][20] President Viktor Yanukovych declared the award illegal, since Bandera was never a citizen of Ukraine, a stipulation necessary for getting the award. This announcement was confirmed by a court decision in April 2010.[21] In January 2011, the award was officially annulled.[22][23] A proposal to confer the award on Bandera was rejected by the Ukrainian parliament in August 2019.[24]

Bandera remains a highly controversial figure in Ukraine,[25][26][27] with some Ukrainians hailing him as a role model hero,[28] liberator who fought against the Soviet Union, Poland and Nazi Germany trying to establish an independent Ukraine, while other Ukrainians condemn him as a fascist[29] and a war criminal[29] who was, together with his followers, largely responsible for the massacres of Polish civilians[30] and partially for the Holocaust.[31][32][33][34]

Early life

Bandera was born on 1 January 1909 in Staryi Uhryniv, Galicia, Austria-Hungary to Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church priest Andriy Bandera (1882–1941) and Myroslava (1890–1921) who died of tuberculosis when Bandera was still a child. He did not attend a primary school due to the WWI and was taught at home by his parents. Young Bandera also sang in a choir, played guitar, mandolin, enjoyed hiking, jogging, swimming, ice skating, and basketball. After graduation from a Ukrainian high school in 1927, where he was engaged in a number of youth organizations, Bandera planned to attend the Husbandry Academy in Czechoslovakia, but he either did not get a passport or the Academy notified him that it was closed. In 1928, Bandera enrolled in the agronomy program at the Politechnika Lwowska in Lwów but never completed his studies due to his political activities and arrests.[4]

Pre-World War II activity

Early activities

Stepan Bandera had met and associated himself with members of a variety of Ukrainian nationalist organizations throughout his schooling—from Plast, to the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (Ukrainian: Українська Визвольна Організація) and also the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) (Ukrainian: Організація Українських Націоналістів). The most active of these organizations was the OUN, and the leader of the OUN was Andriy Melnyk.[citation needed]

Stepan Bandera quickly rose through the ranks of these organizations, becoming the chief propaganda officer of the OUN in 1931, the second in command of OUN in Galicia in 1932–1933, and the head of the National Executive of the OUN in 1933. In the early 1930s, Bandera was very active in finding and developing groups of Ukrainian nationalists in both Western and Eastern Ukraine.[citation needed]

OUN

Bandera joined OUN in 1929, quickly climbed through the ranks and became head of the OUN national executive in Galicia in June 1933.[4] He expanded the OUN's network in the Kresy, directing it against both Poland and the Soviet Union. To stop expropriations, Bandera turned OUN against the Polish officials who were directly responsible for anti-Ukrainian policies. Activities included mass campaigns against Polish tobacco and alcohol monopolies and against the denationalization of Ukrainian youth. He was arrested in Lviv in 1934, and tried twice: first, concerning involvement in a plot to assassinate the minister of internal affairs, Bronisław Pieracki, and second at a general trial of OUN executives. He was convicted of terrorism and sentenced to death. The death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.[4]

According to various sources, Bandera was freed on September 13, 1939, either by Ukrainian jailers after Polish jail administration left the jail,[35] by Poles[36] or by the Nazis soon after the German invasion of Poland.[37][38][39][4]

Soon thereafter Eastern Poland was occupied by the Soviet Union. Upon release from prison, Bandera moved to Kraków, the capital of Germany's occupational General Government. There, he came in contact with the leader of the OUN, Andriy Atanasovych Melnyk. In 1940, the political differences between the two leaders caused the OUN to split into two factions that argued which one was legitimate.[40] The OUN-M faction led by Melnyk preached a more conservative approach to nation-building, while the OUN-B faction, led by Bandera, supported a revolutionary approach.[41]

Formation of Mobile Groups

Before the independence proclamation of 30 June 1941, Bandera oversaw the formation of so-called "Mobile Groups" (Ukrainian: мобільні групи) which were small (5–15 members) groups of OUN-B members who would travel from General Government to Western Ukraine and, after a German advance to Eastern Ukraine, encourage support for the OUN-B and establish local authorities run by OUN-B activists.[42]

In total, approximately 7,000 people participated in these mobile groups, and they found followers among a wide circle of intellectuals, such as Ivan Bahriany, Vasyl Barka, Hryhorii Vashchenko and many others.[citation needed]

Formation of the UPA

World War II

Prior to 1939 invasion of Poland, German military intelligence recruited OUN members into Bergbauernhilfe unit, also smuggled Ukrainian nationalists into Poland in order to erode Polish defences by conducting a terror campaign directed at Polish farmers and Jews. OUN leaders Andriy Melnyk (code name Consul I) and Bandera (code name Consul II) both served as agents of the Nazi Germany military intelligence Abwehr Second Department. Their goal was to run diversion activities after Germany's attack on the Soviet Union. This information is part of the testimony that Abwehr Colonel Erwin Stolze gave on 25 December 1945 and submitted to the Nuremberg trials, with a request to be admitted as evidence.[43][44][45][46][47]

In the spring of 1941, Bandera held meetings with the heads of Germany's intelligence, regarding the formation of "Nachtigall" and "Roland" Battalions. In spring of that year the OUN received 2.5 million marks for subversive activities inside the Soviet Union.[42][48] Gestapo and Abwehr officials protected Bandera followers, as both organizations intended to use them for their own purposes.[49]

On June 23, 1941, one day prior to German attack on the Soviet Union, Bandera sent a letter to Hitler reasoning the case for an independent Ukraine.[6] On 30 June 1941, with the arrival of Nazi troops in Ukraine, Bandera and the OUN-B unilaterally declared an independent Ukrainian state ("Act of Renewal of Ukrainian Statehood").[50] The proclamation pledged a cooperation of the new Ukrainian state with Nazi Germany under the leadership of Hitler with a closing note "Glory to the heroic German army and its Führer, Adolf Hitler".[5] The declaration was accompanied by violent pogroms.[50]

Bandera's expectation that the Nazi regime would post factum recognize an independent fascist Ukraine as an Axis ally proved to be wrong.[50] In 1941 relations between Nazi Germany and the OUN-B had soured to the point where a Nazi document dated 25 November 1941 stated that "... the Bandera Movement is preparing a revolt in the Reichskommissariat which has as its ultimate aim the establishment of an independent Ukraine. All functionaries of the Bandera Movement must be arrested at once and, after thorough interrogation, are to be liquidated...".[51] On 5 July, Bandera was placed under arrest and taken to Berlin the next day. On 12 July, the prime minister of the newly formed Ukrainian National Government, Yaroslav Stetsko, was also arrested and taken to Berlin. Although released from custody on 14 July, both were required to stay in Berlin. On 15 September 1941 Bandera and leading OUN members were arrested by the Gestapo.

In January 1942, Bandera was transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp's special prison cell building (Zellenbau) for high-profile political prisoners.[52] In April 1944, Bandera and his deputy Yaroslav Stetsko were approached by a Reich Security Main Office official to discuss plans for diversions and sabotage against the Soviet Army.[53] In September 1944,[54] Bandera was released by the German authorities and allowed to return to Ukraine in the hope that his partisans would harass the Soviet troops, which by that time had handed the Germans major defeats.

Postwar activity

Shortly after the war, Bandera and his family moved several times around West Germany before settling in Munich. He used false identification documents that helped him to conceal his past relationship with the Nazis.[4] Bandera was protected by the Gehlen Organization but he also received help from underground organizations of former Nazis who helped Bandera to cross borders between Allied occupation zones.[4]

According to Stephen Dorril, author of MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty's Secret Intelligence Service, OUN-B was re-formed in 1946 under the sponsorship of MI6. The organization had been receiving some support from MI6 since the 1930s.[55] One faction of Bandera's organization, associated with Mykola Lebed, became more closely associated with the CIA.[56] Bandera himself was the target of an extensive and aggressive search carried out by the Counterintelligence Corps (CIC).[9] It failed, having described their quarry as "extremely dangerous" and "constantly en route, frequently in disguise".[9] Some American intelligence reported that he even was guarded by former SS men.[57]

Also in 1946, agents of the CIC and NKVD entered into extradition negotiations based on the intra-Allied cooperation wartime agreement made at the Yalta Conference. The CIC wanted Frederick Wilhelm Kaltenbach, who would turn out to be deceased, and in return the Soviet Union proposed Bandera. Bandera and many Ukrainian nationalists had ended up in the American zone after the war. The Soviet Union regarded all Ukrainians as Soviet citizens and demanded their repatriation under the intra-Alied agreement. The US thought Bandera was too valuable to give up due to his knowledge about the Soviet Union, so the US started blocking his extradition under an operation called "Anyface". From the perspective of the US, the Soviet Union and Poland were issuing extradition attempts of these Ukrainians to prevent the US from getting sources of intelligence, so this became one of the factors in the breakdown of the cooperation agreement.[58]

Bandera's organization perpetrated many crimes, including hundreds of thousands of murders,[50] counterfeiting, and kidnapping. After the Bavarian state government initiated a crackdown on it, Bandera reached an agreement with the BND, offering them his service, despite CIA warning the West Germans against cooperating with him.[9] Bandera also visited after the war Ukrainian communities in Canada, Austria, Italy, Spain, Belgium, UK and Holland.[4]

His views

According to Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe "Bandera's worldview was shaped by numerous far-right values and concepts including ultranationalism, fascism, racism, and antisemitism; by fascination with violence; by the belief that only war could establish a Ukrainian state; and by hostility to democracy, communism, and socialism. Like other young Ukrainian nationalists he combined extremism with religion and used religion to sacralize politics and violence."[59]

Swedish-American historian Per Anders Rudling said that Bandera and his followers "advocated the selective breeding to create a "pure" Ukrainian race[60] and that "the OUN shared the fascist attributes of antiliberalism, anticonservatism, and anticommunism, an armed party, totalitarianism, anti-Semitism, Führerprinzip, and an adoption of fascist greetings. Its leaders eagerly emphasized to Hitler and Ribbentrop that they shared the Nazi Weltanschauung and a commitment to a fascist New Europe."[61]

These statements of Rudling became the subject of international attention in 2012 when a group of Ukrainian organizations in Canada delivered a signed protest to his employer, accusing him of betraying his own university's principles.[62][63]

American historian Timothy Snyder has described Bandera as a fascist.[3]

Views towards Poles

In a May 1941 meeting in Kraków, the leadership of Bandera's OUN faction adopted the program "Struggle and action for OUN during the war" (Ukrainian: "Боротьба й діяльність ОУН під час війни") which outlined the plans for activities at the onset of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union and the western territories of the Ukrainian SSR.[64] Section G of that document, the "Directives for organizing the life of the state during the first days" (Ukrainian: "Вказівки на перші дні організації державного життя"), outline activity of the Bandera followers during summer 1941.[65]

In late 1942, when Bandera was in a German concentration camp, his organization, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, was involved in a massacre of Poles in Volhynia and, in early 1944, ethnic cleansing also spread to Eastern Galicia. It is estimated that more than 35,000 and up to 60,000 Poles, mostly women and children along with unarmed men, were killed during the spring and summer campaign of 1943 in Volhynia, and up to 133,000 if other regions, such as Eastern Galicia, are included.[66][67][68]

Despite the central role played by Bandera's followers in the massacre of Poles in western Ukraine, Bandera himself was interned in a German concentration camp when the concrete decision to massacre the Poles was made and when the Poles were killed.[clarification needed] According to Yaroslav Hrytsak, Bandera was not completely aware of events in Ukraine during his internment from the summer of 1941 and had serious differences of opinion with Mykola Lebed, the OUN-B leader who remained in Ukraine and who was one of the chief architects of the massacres of Poles.[69][70][unreliable source?]

Views towards Jews

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

Ukrainian nationalism did not historically include antisemitism as a core aspect of its program and saw Russians as well as Poles as the chief enemy with Jews playing a secondary role.[71] Nevertheless, Ukrainian nationalism was not immune to the influence of the antisemitic climate in Eastern and Central Europe,[71] that had already become highly racialized in the late 19th century.

One of the political differences between Bandera and Andriy Melnyk was their attitude about the fact that Richard Jary, Mykola Stsibors’kyi and other members of the OUN were married to Jewish women. For Bandera that was an utter scandal: in a letter he wrote to Melnyk on 10th August 1940, he said he would accept his leadership, provided that he expelled OUN members who were married to Jewish women.[40] Hostility to both the Soviet central government and the Jewish minority was highlighted at the OUN-B's Conference in Kraków in May 1941, at which the leadership of Bandera's OUN faction adopted the program "Struggle and action of OUN during the war" which outlined the plans for activities at the onset of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union and the western territories of the Ukrainian SSR.[64] The program declared:

Section G of the program – "Directives for organizing the life of the state during the first days" outlined activity of the Bandera followers during mid-1941.[65] In a subsection on "Minority Policy", the leaders of OUN-B ordered:

Later in June, Yaroslav Stetsko sent to Bandera a report in which he stated "We are creating a militia which will help to remove the Jews and protect the population."[75][76] Leaflets spread in the name of Bandera in the same year called for the "destruction" of "Moscow", Poles, Hungarians and Jewry.[77][78][79] In 1941–1942 while Bandera was cooperating with the Germans, OUN members did take part in anti-Jewish actions. German police in 1941 reported that "fanatic" Bandera followers, organised in small groups were "extraordinarily active" against Jews and communists.[80]

UPA forced an unknown number of Jewish doctors, dentists, and nurses to treat UPA insurgents. The majority were later murdered shortly before the Soviet arrival.[4][81][82] In the official organ of the OUN-B's leadership, instructions to OUN groups urged those groups to "liquidate the manifestations of harmful foreign influence, particularly the German racist concepts and practices."[83] Several Jews took part in Bandera's underground movement,[83] including one of Bandera's close associates Richard Yary who was also married to a Jewish woman. Another notable Jewish UPA member was Leyba-Itzik "Valeriy" Dombrovsky. (While two Karaites from Galicia, Anna-Amelia Leonowicz (1925–1949) and her mother, Helena (Ruhama) Leonowicz (1890–1967), are reported to have become members of OUN, oral accounts suggest that both women collaborated not of their own free will, but following threats from nationalists.[84]) By 1942, Nazi officials had concluded that Ukrainian nationalists were largely indifferent to Jews and were willing to both help them or kill them if either better served the nationalist cause. A report, dated 30 March 1942, sent to the Gestapo in Berlin, claimed that "the Bandera movement provided forged passports not only for its own members but also for Jews."[85] The false papers were most likely supplied to Jewish doctors or skilled workers who could be useful for the movement.[86]

German-Polish historian Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe considers Bandera an antisemite.[59]

Death

Starting 1954, the Soviet KGB, multiple times attempted to kidnap or assassinate Bandera.[4] On 15 October 1959, Bandera collapsed outside of Kreittmayrstrasse 7 in Munich and died shortly thereafter. A medical examination established that the cause of his death was poison by cyanide gas.[87][88] On 20 October 1959, Bandera was buried in the Waldfriedhof Cemetery in Munich. His wife and three children moved to Toronto, Canada.[4] After his assassination, Bandera’s admirers among Ukrainian diaspora portrayed his death as one of the most important tragedies in Ukrainian history, transformed him into a martyr killed by an enemy of the Ukrainians.[4]

Two years after his death, on 17 November 1961, the German judicial bodies announced that Bandera's murderer had been a KGB agent named Bohdan Stashynsky who used a cyanide dust spraying gun to murder Bandera and acted on the orders of Soviet KGB head Alexander Shelepin and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev.[9][89] After a detailed investigation against Stashynsky, who by then had defected from KGB and confessed the killing, a trial took place from 8 to 15 October 1962. Stashynsky was convicted, and on 19 October he was sentenced to eight years in prison.

Family

Bandera's brothers, Oleksandr and Vasyl, were arrested by the Germans and sent to Auschwitz concentration camp where they were allegedly killed by Polish inmates in 1942.[90]

His father Andriy was arrested by the Soviets in late May 1941 for harboring an OUN member and transferred to Kyiv. On 8 July he was sentenced to death and executed on the 10th. His sisters Oksana and Marta–Maria were arrested by the NKVD in 1941 and sent to a gulag in Siberia. Both were released in 1960 without the right to return to Ukraine. Marta–Maria died in Siberia in 1982, and Oksana returned to Ukraine in 1989 where she died in 2004. Another sister, Volodymyra, was sentenced to a term in Soviet labor camps from 1946 to 1956. She returned to Ukraine in 1956.[91]

Legacy

According to The Guardian, "Post-war Soviet history propagated the image of Bandera and the UPA as exclusively fascist collaborators and xenophobes."[92] On the other hand, with the rise of nationalism in Ukraine, his memory there has been elevated.

In an interview with the Russian newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda in 2005, former KGB Chief Vladimir Kryuchkov claimed that "the murder of Stepan Bandera was one of the last cases when the KGB disposed of undesired people by means of violence."[93]

In late 2006, the Lviv city administration announced the future transference of the tombs of Stepan Bandera, Andriy Melnyk, Yevhen Konovalets and other key leaders of OUN/UPA to a new area of Lychakiv Cemetery specifically dedicated to victims of the repressions of the Ukrainian national liberation struggle.[94]

In October 2007, the city of Lviv erected a statue dedicated to Bandera.[95] The appearance of the statue has engendered a far-reaching debate about the role of Stepan Bandera and UPA in Ukrainian history. The two previously erected statues were blown up by unknown perpetrators; the current is guarded by a militia detachment 24/7. On 18 October 2007, the Lviv City Council adopted a resolution establishing the Award of Stepan Bandera.[96][97]

On 1 January 2009, his 100th birthday was celebrated in several Ukrainian centres[98][99][100][101][102] and a postage stamp with his portrait was issued the same day.[103] On 1 January 2014, Bandera's 105th birthday was celebrated by a torchlight procession of 15,000 people in the centre of Kyiv and thousands more rallied near his statue in Lviv.[104][105][106] The march was supported by the far-right Svoboda party and some members of the center-right Batkivshchyna.[107]

In 2018, the Ukrainian Parliament designated the 1 January, the Bandera's birthday, as a national holiday.[108] The decision was criticized by the Jewish organization Simon Wiesenthal Center.[109]

Attitudes in Ukraine towards Bandera

Bandera continues to be a divisive figure in Ukraine. Although Bandera is venerated in certain parts of western Ukraine, and 33% of Lviv's residents consider themselves to be followers of Bandera,[110] he, along with Joseph Stalin and Mikhail Gorbachev, is considered in surveys of Ukraine as a whole among the three historical figures who produce the most negative attitudes.[111]

A national survey conducted in Ukraine in 2009 inquired about attitudes by region towards Bandera's faction of the OUN. It produced the following results:[112]

Attitudes by region towards Bandera's faction of the OUNRegionVery positiveMostly positiveNeutralMostly negativeVery negativeUnsureGalicia (Lviv, Ternopil, Ivano-Frankivsk) 37 26 20 5 6 6

Volhynia 5 20 57 7 5 6

Transcarpathia 4 32 50 0 7 7

Central Ukraine (Kyiv, Zhytomyr, Cherkasy, Chernihiv, Poltava, Sumy, Vinnytsia, Kirovohrad) 3 10 24 17 21 25

Eastern Ukraine (Donetsk, Luhansk, Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhia) 1 1 19 13 26 20

Southern Ukraine (Odessa, Mykolaiv, Kherson, Crimea) 1 1 13 31 48 25

Ukraine as a whole 6 8 23 15 30 18

Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Bandera's favorability shot up rapidly, with 74% of Ukrainians now viewing him favorably, according to a poll in April 2022. Bandera continues to cause friction with countries such as Poland and Israel.[28] During the war, Russia heavily promoted the theme of "denazification", and used rhetoric that was similar to Soviet era policy of equating the development of Ukrainian national identity with Nazism due to Bandera's collaboration, which has a particular resonance in Russia.[114]

2014 Russian intervention in Ukraine

During the 2014 Crimean crisis and unrest in Ukraine, pro-Russian Ukrainians, Russians (in Russia), and some Western authors alluded to the bad influence of Bandera on Euromaidan protesters and pro-Ukrainian Unity supporters in justifying their actions.[115] According to The Guardian, " The term “Banderite” to described his followers gained a recent new and malign life when Russian media used it to demonise Maidan protesters in Kiev, telling people in Crimea and east Ukraine that gangs of Banderites were coming to carry out ethnic cleansing of Russians."[92] Russian media used this to justify Russia's actions.[29] Putin welcomed the annexation of Crimea by declaring that he "was saving them from the new Ukrainian leaders who are the ideological heirs of Bandera, Hitler's accomplice during World War II."[29] Pro-Russian activists claimed: "Those people in Kyiv are Bandera-following Nazi collaborators."[29] Ukrainians living in Russia complained of being labelled a "Banderite", even when they were from parts of Ukraine where Bandera has no popular support.[29] Groups who idolize Bandera took part in the Euromaidan protests but were a minority element.[29][116]

Hero of Ukraine award

On 22 January 2010, on the Day of Unity of Ukraine, the then-President of Ukraine Viktor Yushchenko awarded to Bandera the title of Hero of Ukraine (posthumously) for "defending national ideas and battling for an independent Ukrainian state."[117] A grandson of Bandera, also named Stepan, accepted the award that day from the Ukrainian President during the state ceremony to commemorate the Day of Unity of Ukraine at the National Opera House of Ukraine.[117][118][119][120]

Reactions to Bandera's award vary. This award has been condemned by the Simon Wiesenthal Center[121] and the Student Union of French Jews.[122] On 25 February 2010, the European Parliament criticized the decision by then president of Ukraine, Yushchenko to award Bandera the title of Hero of Ukraine and expressed hope it would be reconsidered.[123] On 14 May 2010, in a statement, the Russian Foreign Ministry said about the award: "that the event is so odious that it could no doubt cause a negative reaction in the first place in Ukraine. Already it is known a position on this issue of a number of Ukrainian politicians, who believe that solutions of this kind do not contribute to the consolidation of Ukrainian public opinion".[124] On the other hand, the decree was applauded by Ukrainian nationalists in western Ukraine and by a small portion of Ukrainian Americans.[125][126]

On 5 March 2010, President Viktor Yanukovych stated that he would make a decision to repeal the decrees to honor the title of Heroes of Ukraine to Bandera and fellow nationalist Roman Shukhevych before the next Victory Day,[127] although the Hero of Ukraine decrees do not stipulate the possibility that a decree on awarding this title can be annulled.[128] On 2 April 2010, an administrative Donetsk region court ruled the presidential decree awarding the title to be illegal. According to the court's decision, Bandera was not a citizen of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (vis-à-vis Ukraine).[129][130][131][132] On 5 April 2010, the Constitutional Court of Ukraine refused to start constitutional proceedings on the constitutionality of the President Yushchenko decree the award was based on. A ruling by the court was submitted by the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea on 20 January 2010.[133] In January 2011, the presidential press service informed that the award was officially annulled.[22][134] This was done after a cassation appeal filed against the ruling by Donetsk District Administrative Court was rejected by the Higher Administrative Court of Ukraine on 12 January 2011.[135][136] Former President Yushchenko called the annulment "a gross error."[137]

In December 2018, the Ukrainian parliament moved to again confer the award on Bandera but the proposal was rejected in August 2019.[24]

Commemoration

There are Stepan Bandera museums in Dubliany, Volia-Zaderevatska, Staryi Uhryniv, and Yahilnytsia. There is a Stepan Bandera Museum of Liberation Struggle in London, part of the OUN Archive,[138] and The Bandera's Family Museum (Музей родини Бандерів) in Stryi.[139][140] There are also Stepan Bandera streets in Lviv (formerly vulytsia Myru, "Peace street"), Lutsk (formerly Suvorovska street), Rivne (formerly Moskovska street), Kolomyia, Ivano-Frankivsk, Chervonohrad (formerly Nad Buhom street),[141] Berezhany (formerly Cherniakhovskoho street), Drohobych (formerly Sliusarska street), Stryi, Kalush, Kovel, Volodymyr-Volynskyi, Horodenka, Dubrovytsia, Kolomyia, Dolyna, Iziaslav, Skole, Shepetivka, Brovary, and Boryspil, and a Stepan Bandera Avenue in Ternopil (part of the former Lenin Avenue).[142] On 16 January 2017, the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance stated that of the 51,493 streets, squares and "other facilities" that had been renamed (since 2015) due to decommunization 34 streets were named after Stepan Bandera.[143] Due to "association with the communist totalitarian regime", the Kyiv City Council on 7 July 2016 voted 87 to 10 in favor of supporting renaming Moscow Avenue to Stepan Bandera Avenue.[144][145]

After the fall of the Soviet Union, monuments dedicated to Stepan Bandera have been constructed in a number of western Ukrainian cities and villages, including a statue in Lviv. Bandera was also named an honorary citizen of a number of western Ukrainian cities.[4]

In late 2018, the Lviv Oblast Council decided to declare the year of 2019 to be the year of Stepan Bandera, sparking protests by Israel.[146] Two feature films have been made about Bandera, among them are Assassination: An October Murder in Munich (1995) and The Undefeated (2000), both directed by Oles Yanchuk, along with a number of documentary films. In 2021, the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory under the authority of the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture, included Bandera, among other Ukrainian nationalist figures, in Virtual Necropolis, a project intended to commemorate historical figures important for Ukraine.[147]

Annexations by Poland in 1938 OR HOW WORLD WAR II STARTED....DAY ONE OF WWII !!!

Within the region originally demanded from Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany in 1938 was a

n important railway junction city of Bohumín. The Poles regarded the city as of crucial importance to the area and to Polish interests. On 28 September, Beneš composed a note to the Polish administration offering to reopen the debate surrounding the territorial demarcation in Těšínsko in the interest of mutual relations, but he dlayed in sending it in hopes of good news from London and Paris, which came only in a limited form. Beneš then turned to the Soviet leadership in Moscow, which begun a partial mobilisation in eastern Belarus and the Ukrainian SSR and threatened Poland with the dissolution of the Soviet-Polish non-aggression pact.[4]

Nevertheless, the Polish leader, Colonel Józef Beck believed that Warsaw should act rapidly to forestall the German occupation of the city. At noon on 30 September, Poland gave an ultimatum to the Czechoslovak government. It demanded the immediate evacuation of Czechoslovak troops and police and gave Prague time until noon the following day. At 11:45 a.m. on 1 October the Czechoslovak foreign ministry called the Polish ambassador in Prague and told him that Poland could have what it wanted. The Polish Army, commanded by General Władysław Bortnowski, annexed an area of 801.5 km² with a population of 227,399 people.

The Germans were delighted with this outcome. They were happy to give up a provincial rail centre to Poland; it was a small sacrifice indeed. It spread the blame of the partition of Czechoslovakia, made Poland a seeming accomplice in the process and confused the issue as well as political expectations. Poland was accused of being an accomplice of Nazi Germany – a charge that Warsaw was hard put to deny.[5] Poland occupied some northern parts of Slovakia and received from Czechoslovakia Zaolzie, territories around Suchá Hora and Hladovka, around Javorina, and in addition the territory around Lesnicadisambiguation needed in the Pieniny Mountains, a small territory around Skalité and some other very small border regions (they officially received the territories on 1 November 1938 (see also Munich Agreement and First Vienna Award).

Territorial changes on the (Czecho)Slovak-Polish border between 1902–1945 (red parts – to Austrian Galicia/Poland; green parts – to Czechoslovakia/Slovakia)

https://ausertimes.blogspot.com/2022/07/whyto-poke-fun-truly-car-assassination.html

https://ausertimes.blogspot.com/2022/07/greek-bailout-was-also-great-robbery-of.html

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment