FUTURE WAR ON BALKANS AGAINST CROATIA UNLESS I WOULD OPT FOR CROATIAN KINGDOM OPTION WHICH I NEVER EVER WILL OR WOULD.

‘Everyone loved each other’: the rise of Yugonostalgia

While many citizens of the former Yugoslavia miss the lower prices and global recognition, others warn against over-romanticising the Tito era

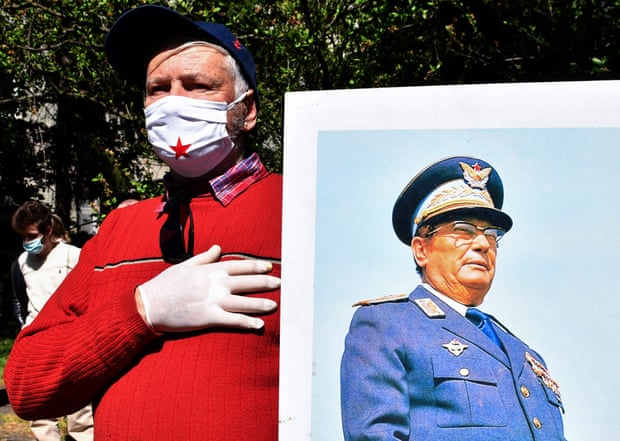

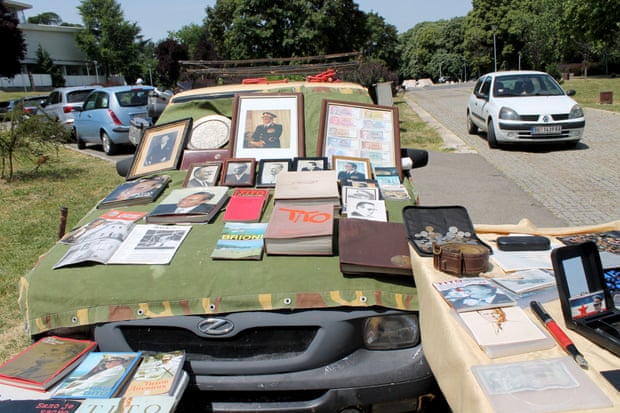

On a recent day in Belgrade, as the sun beat down, coaches pulled up and departed outside the Museum of Yugoslavia, an imposing mid-century block in the Serbian capital. A steady trickle of people emerged, some carrying flowers and a few waving the country’s old flag. They had come to visit the mausoleum that houses the grave of Josep Broz Tito, the founder of socialist Yugoslavia.

Many of the visitors had grown up under the old system and had come to mark the dictator’s birthday, which was a major public holiday before Yugoslavia’s disintegration. Some belonged to far-left political parties, and sported kitsch-looking T-shirts and banners.

But there were also a few younger people. On the steps outside a special exhibition examining the Tito years via posters, artworks, artefacts and the recorded memories of “common people”, I met 18-year-old Milos Tomcic wearing the hat and scarf of the ‘pioneers’, the Yugoslav socialist youth movement.

“I wanted to see a picture of that time,” he said, when I asked why he had come. “It was a great time. Everyone loved each other.” Did he consider himself Serbian or Yugoslavian? “Yugoslavian,” he replied, without hesitation. “My mum is Serbian, my dad Montenegrin, my grandma Croatian. Actually, my family is from all over Yugoslavia.”

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, made up of six republics –Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Slovenia, Montenegro and North Macedonia, plus the then autonomous region of Kosovo – was established by Tito in 1945.

Tito’s state aimed to unite the region’s different ethnic and religious groups under the slogan “unity and brotherhood”. Rising nationalism after his death in 1980 led to its breakup in 1992 and the bloody Yugoslav wars of the 1990s.

A common narrative during these years was that Tito had, for nearly half a century, forced different peoples to live together against their wishes. But 30 years on, many still hold deep affection for the country that no longer exists and regret its dissolution.

Fondness for the old system is often referred to as “Yugonostalgia”. However, Larisa Kutovic, a political anthropologist from Sarajevo who studies post-Yugoslav identity in Bosnia, is cautious about the term. “Nostalgia implies some kind of melancholy or longing,” she says. Of course this exists, with many restaurants and guesthouses around the region, such as the famous Café Tito in Sarajevo, festooned in kitschy memorabilia and presenting a rose-tinted view of the era. But Kutovic says there is also a movement of younger people who look more critically at the period, assessing both its positives and negatives.

“There’s a great deal of appreciation for the socialist period, and it’s associated with economic growth and vast improvements in the standards of living,” she says, adding that the Yugoslav project’s “failed promises” paled in comparison to the nationalism and violence that followed. Most ex-Yugoslav states have seen huge economic decline since the wars and still suffer high levels of brain drain.

Bosnia and Serbia in particular are plagued by political strife, and their once utopian brutalist housing estates and Yugoslav-built railways sit decaying. Although Croatia and Slovenia have found relative stability as EU members, other countries’ applications have stalled and negotiations failed to materialise, leaving many doubting whether they will ever join the bloc.

Against this backdrop, some wonder whether the past could hold any solutions for the future. Kutovic cites the workers’ rights movements that have sprung up in Bosnia over the last decade, based on the old Yugoslav socialist model of worker self-organisation. “This system was very specific to Yugoslavia,” she says, explaining its divergence from Stalinist state-ownership of industry.

Although Yugoslavia was a one-party state, there were distinct differences from other iron curtain countries. Tito founded the non-aligned movement and maintained balanced relationships between the west and the USSR, and Yugoslav citizens could travel to either region. The strength of the old Yugoslav passport is mentioned by many of those I meet visiting Tito’s grave who now require visas to enter most countries.

Another common theme Kutovic sees is a loss of status, and a perception that people have gone from living in a relatively large, well-respected country to much smaller, less significant ones. George Peraloc was born in North Macedonia in 1989 but now lives in Bangkok. “Whenever I have to do something bureaucratic like open a bank account here, they can never find North Macedonia on their system, but they can find Yugoslavia,” he told me.

“If you ask me, we could still benefit from a federation, even if it’s not Yugoslavia, because we’re so small and insignificant on our own.” He believes these feelings are common among people of his age, who never actually lived under the old system. “All our infrastructure is from that period, and now it’s falling apart,” he adds.

There are also emerging movements that re-examine the region’s anti-fascist, anti-nationalist heritage, which the wars revised or sought to erase. Choirs singing old partisan songs have sprung up, both in the Balkans and among diaspora communities.

In Vienna, the 29 November choir, named after the date Yugoslavia was founded, consists of members from all ex-Yugoslav countries. Its initial aim was to challenge the nationalism that rose in the diaspora community during and after the wars. Yugoslav workers’ clubs, where people had formerly met to drink coffee, chat and play chess, had become segregated by ethnicity.

Choir members dress in red and blue jackets with stars, referencing the old Yugoslav flag, but they avoid singing songs associated with the Communist party or that celebrate Tito.

“That’s a conscious decision because we know there’s a glorification happening, which is problematic,” says conductor Jana Dolecki, who is originally from Croatia and moved to Vienna in 2013. “Plus, they didn’t really have any good songs,” she laughs.

The choir has helped some members explore a sensitive period of history. Marko Marković, who was born in Belgrade but grew up in Vienna, says his family refused to discuss the wars with him as a child. “It was too complicated for a seven-year-old to understand, or so they thought,” he remembers. “So I always had the feeling that the history of where I came from is a taboo topic.” When he found the choir, he felt he could finally “patch up some holes.”

The internet also provides a gateway for people to rediscover overlooked aspects of their heritage. Several popular Instagram accounts collate the furniture, brutalist architecture and graphic design of the period.

Peter Korchnak, who grew up in then Czechoslovakia, launched the Remembering Yugoslavia podcast in 2020. “Growing up, Yugoslavia seemed like a paradise to me,” he says, explaining that many people fleeing the Czechoslovakian regime would escape to Yugoslavia. Dissidents from other communist countries, such as Ceaușescu-era Romania, often did the same.

“We watched the violent dissolution of Yugoslavia while I witnessed my own country’s peaceful dissolution,” he says. “I started looking for comparisons, comparing the two. And I just became fascinated by it.”

Korchnak has been struck by the emotional outpouring he receives from some listeners. “The best comment I’ve heard is that it’s like a public service,” he says. “And a lot of people say, ‘For a long time I was ashamed to even think the word ‘Yugoslavia’. Some have said it’s even been like therapy.”

Korchnak finds the fondness many ex-Yugoslavs have for their old system striking. “You might hear older people [in Czechia] saying, ‘Oh, things were cheaper back then,’ but mostly everyone has moved on,” he says. “But [in ex-Yugoslavia] it’s kind of transformed into something else.”

However, some are more critical of what they see as an over-romanticism of the period. Arnela Išerić’s family are from Bosnia and fled to the US, where she was raised during the war. “My impression as a child was that [Yugoslavia] was the most wonderful time and everything was harmonious,” she says. “But when I grew up, I realised there were things about it I did not like.” She cites the lack of LGBT rights and suppression of political dissent. However, she says she can still identify with the “spirit” of Yugoslavia.

“When I travel to other parts of the region, such as Montenegro or Croatia, I always feel like I connect with people. I can speak their language and we have a similar culture.”

As time moves on and younger people are less directly affected by the trauma of war, some feel it’s becoming easier to analyse the period. “Almost every day, someone is asking if they can interview us for their dissertation on post-Yugoslav identity,” says Dolecki, the choir conductor. “For a long time it was a socially taboo topic,” agrees her colleague Marković. “But this generation has the luxury of being far enough away to not have all the biases, and the trauma that comes with it. And I think this will become bigger.”

Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia

| Alexander | |

|---|---|

| Crown Prince of Yugoslavia | |

Crown Prince Alexander receiving the rank of Commander of the Légion d’Honneur, 15 May 2015 | |

| Head of the House of Karađorđević | |

| Tenure | 3 November 1970 – present |

| Predecessor | Peter II |

| Heir apparent | Philip |

| Born | 17 July 1945 Claridge's, Mayfair, London[a] |

| Spouse | Princess Maria da Gloria of Orléans-Braganza (m. 1972; div. 1985) |

| Issue | |

| House | Karađorđević |

| Father | Peter II of Yugoslavia |

| Mother | Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark |

| Religion | Serbian Orthodox |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1966–1972 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | 16th/5th The Queen's Royal Lancers |

| Serbian and Yugoslav royal family |

|---|

The Crown Prince show Extended royal family |

Alexander, Crown Prince of Yugoslavia (born 17 July 1945 in London), is the head of the House of Karađorđević, the former royal house of the defunct Kingdom of Yugoslavia and its predecessor the Kingdom of Serbia. Alexander is the only child of King Peter II and his wife, Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark. He held the position of crown prince in the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia for the first four-and-a-half months of his life, from his birth until the declaration of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia later in 1945. In public he is also claiming the crowned royal title of "Alexander II Karađorđević" (Serbian Cyrillic: Александар II Карађорђевић / Aleksandar II Karađorđević) although he is not king or crowned.

Born and raised in the United Kingdom, he enjoys close relationships with his relatives in the British royal family. His godparents were King George VI of the United Kingdom and his daughter, the then-Princess Elizabeth (now Queen Elizabeth II). Through his father Alexander is a direct descendant of Queen Victoria, through his great-great-grandfather Prince Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Victoria's second eldest son. Maternally he is also a direct descendant of Queen Victoria, through his great-great-grandmother Victoria, Empress of Germany, Victoria's eldest daughter. Alexander is known for his support of monarchism and his humanitarian work.

Status at birth[edit]

As with many other European monarchs during World War II, King Peter II left his country to establish a government-in-exile.[1] He left Yugoslavia in April 1941 and arrived in London in June 1941. The Royal Yugoslav Armed Forces capitulated in 18 April.

After the Tehran Conference, the Allies shifted support from royalist Chetniks to communist-led Partisans.[2] Commenting on the event and what happened to his father, Crown Prince Alexander said, "He [Peter II] was too straight. He could not believe that his allies–the mighty American democracy and his relatives and friends in London–could do him in. But that's precisely what happened".[3] In June 1944 Ivan Šubašić, the Royalist prime minister, and Josip Broz Tito, the Communist Partisan leader, signed an agreement that was an attempt to merge the royal government and communist movement.[citation needed]

On 29 November 1943, AVNOJ (formed by the Partisans) declared themselves the sovereign communist government of Yugoslavia and announced that they would take away all legal rights from the Royal government. On 10 August 1945, less than a month after Alexander's birth, AVNOJ named the country Democratic Federal Yugoslavia. On 29 November 1945, the country was declared a communist republic and changed its name to People's Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.[4]

In 1947, all members of Alexander's family except for his grand-uncle Prince George were deprived of their Yugoslav citizenship[5] and their property was confiscated.[6]

As of 8 July 2015 the High Court in Belgrade found that decree 392, issued by the Presidency of the Presidium of the National Assembly on 3 August 1947, which deprived King Peter II and other members of the House of Karađorđević of their citizenship, was null and void from the moment of its adoption, in the parts pertaining to Crown Prince Alexander, and that all of its legal consequences are thus null and void.[7]

Birth and childhood[edit]

Alexander was born in Suite 212 of Claridge's Hotel in Brook Street, Mayfair, London. The British Government is said to have temporarily ceded sovereignty over the suite in which the birth occurred to Yugoslavia so that the crown prince would be born on Yugoslav territory,[2][8] though the story may be apocryphal, as there exists no documentary record of this. Another part of the story says that a box of soil from the homeland was placed under the bed, so the Prince could be born on Yugoslav soil.[9]

He was the only child of King Peter II and Queen Alexandra of Yugoslavia. He was christened at Westminster Abbey. His godparents were members of the British royal family, King George VI and Princess Elizabeth, now Queen Elizabeth II.[2]

His parents were relatively unable to take care of him, due to their various health and financial problems, so Alexander was raised by his maternal grandmother, Princess Aspasia of Greece and Denmark. He was educated at Trinity School, Institut Le Rosey, Culver Military Academy, Gordonstoun, Millfield and Mons Officer Cadet School, Aldershot, and pursued a career in the British military.

Military service[edit]

Alexander graduated from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in 1966 and was commissioned as an officer into the British Army's 16th/5th The Queen's Royal Lancers regiment, rising to the rank of captain. His tours of duty included West Germany, Italy, the Middle East, and Northern Ireland. After leaving the army in 1972, Alexander, who speaks several languages, pursued a career in international business.[10]

Marriages[edit]

On 1 July 1972 at Villamanrique de la Condesa, near Seville, Spain, he married Princess Maria da Gloria of Orléans-Bragança from the Brazilian imperial family. They are double 4th cousins once removed as both are descendants of Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1785–1851) and his wife Princess Maria Antonia von Koháry (1797–1862), as well as of Pedro I, Emperor of Brazil and his wife, Archduchess Maria Leopoldina of Austria.[11] They have three sons: Peter (born 5 February 1980), and fraternal twins: Philip and Alexander (both born 15 January 1982).

Alexander and Maria da Gloria divorced on 19 February 1985. Both of them married for the second time. Maria da Gloria married to Ignacio de Medina, Duke of Segorbe (b. 1947), while Crown Prince Alexander married Katherine Clairy Batis, the daughter of Robert Batis and his wife, Anna Dosti, civilly on 20 September 1985, and religiously the following day, at St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Church, Notting Hill, London. Since their marriage, she is known as Crown Princess Katherine, as per the royal family's website.

Return to Yugoslavia[edit]

Alexander first came to Yugoslavia in 1991. He actively worked with the opposition to Slobodan Milošević and moved to Yugoslavia after Milošević had been deposed in 2000.

On 27 February 2001,[12] the parliament of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) passed legislation conferring citizenship on members of the Karađorđević family. The legislation may also have effectively annulled a decree stripping the family of its citizenship of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) in 1947.

The annulment was the topic of some debate. Notably, the FRY was not the successor of the SFRY; rather the FRY was a new state (and was admitted to the United Nations as a new state on that basis). Therefore, the jurisdiction of a new state to annul an action of a different former state was questioned. In effect, the Karađorđević family had FRY citizenship conferred upon them, not "restored" as such.

The FRY legislation also addresses restoration of property to the Karađorđević family. In March 2001, the property seized from his family, including royal palaces, was returned for residential purposes with property ownership to be decided by parliament at some later date.[citation needed]

He has lived since 17 July 2001 in the Royal Palace (Kraljevski Dvor) in Dedinje, an exclusive area of Belgrade. The Palace, which was completed in 1929, is one of two royal residences in the Royal Compound; the other is the White Palace, which was completed in 1936.

Belief in constitutional monarchy[edit]

Alexander is a proponent of re-creating a constitutional monarchy in Serbia and sees himself as the rightful king. He believes that monarchy could give Serbia "stability, continuity and unity".[13]

A number of political parties and organizations support a constitutional parliamentary monarchy in Serbia. The Serbian Orthodox Church has openly supported the restoration of the monarchy.[14][15] The assassinated former Serbian Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić was often seen in the company of the prince and his family, supporting their campaigns and projects, although his Democratic Party never publicly embraced monarchy.

Crown Prince Alexander has vowed to stay out of politics. He and Princess Katherine spend considerable time engaging in humanitarian work.

The Crown Prince has, however, increasingly participated in public functions alongside the leaders of Serbia, the former Yugoslav republics and members of the diplomatic corps. On 11 May 2006, he hosted a reception at the Royal Palace for delegates attending a summit on Serbia and Montenegro. The reception was attended by the Governor of the National Bank of Serbia, as well as ambassadors and diplomats from Slovenia, Poland, Brazil, Japan, United States, and Austria. He later delivered a keynote speech in front of prime ministers Vojislav Koštunica and Milo Đukanović. In the speech he spoke of prospective Serbian membership of the European Union. He told delegates:[16]

Following Montenegro's successful independence referendum on 21 May 2006, the re-creation of the Serbian monarchy found its way into daily political debate. A monarchist proposal for the new Serbian constitution has been published alongside other proposals. The document approved in October 2006 is a republican one. The Serbian people have not had a chance to vote on the system of government.

The Crown Prince raised the issue of a royal restoration in the immediate aftermath of the vote. In a press release issued on 24 May 2006 he stated:[17]

In 2011 an online open access poll by Serbian middle-market tabloid newspaper Blic showed that 64% of Serbians support restoring the monarchy.[18] Another poll in May 2013 had 39% of Serbians supporting the monarchy, with 32% against it. The public also had reservations with Alexander's apparent lack of knowledge of the Serbian language.[19] On 27 July 2015, newspaper Blic published a poll "Da li Srbija treba da bude monarhija?" ("Should Serbia be a monarchy?"); 49.8% respondents expressed support in a reconstitution of monarchy, 44.6% were opposed and 5.5% were indifferent.[20]

On 16 December 2017, Alexander attended with his wife the state funeral of his first cousin once removed, King Michael of Romania in Bucharest, along with other heads of European royal families and invited guests.[21][22]

No comments:

Post a Comment