Hunting the monkey torturers

A BBC investigation has uncovered a global monkey torture ring. This is the story of the torturers, the amateur sleuths who hunted them, and the fate of Mini, the baby monkey who became a celebrity in their twisted world.

BBC Eye Investigations

ne night last May, unable to sleep, Lucy Kapetanich opened her laptop in the early hours. The screen lit up her tired face in the dark. She typed, “Report a crime to the FBI”, into the search bar and clicked through to the agency’s online tip form. “I have made a complaint before,” she wrote in the little box on the screen. “The monkey hate community is growing.”

Kapetanich was 55 then, a former adult dancer with big green eyes and dyed-black hair that fell in curtains around her face. For the past six months, from her small bedroom in a rundown shared house in Los Angeles, she had been slowly uncovering a global underworld of monkey torture. Her journey had begun in the pandemic, when she was doing daily webcam shows to make ends meet. The long hours on camera were taking a toll on her, so when she clicked off the webcam at night she often opened YouTube, seeking solace in cute animal videos. Her favourites were a chimpanzee family in a zoo in Japan. She could watch them for hours as she drifted towards sleep.

Kapetanich didn’t know it then, but as she watched, YouTube’s algorithm was at work on her, following her every click, saving her every preference, presenting her with new content it hoped she would watch next. Soon, when Kapetanich looked at YouTube at night, monkeys were everywhere. “All it takes is like, one click and bam, it’s all over your feed,” she said.

“The behaviour towards these monkeys is obscene, really grim,” Kapetanich said (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Kapetanich saw monkeys dressed up in baby clothes, monkeys being bathed, forced to walk upright or do other unnatural tasks. Then the algorithm served her videos of monkeys being slapped and sprayed with water. These videos violated YouTube’s terms of service, so she reported them, but the platform didn’t seem to take any action. The videos kept appearing. Kapetanich kept clicking.

Soon enough, a torture video turned up in her feed.

Lucy Kapetanich, aka “Mayhem” (Joel Gunter/BBC)

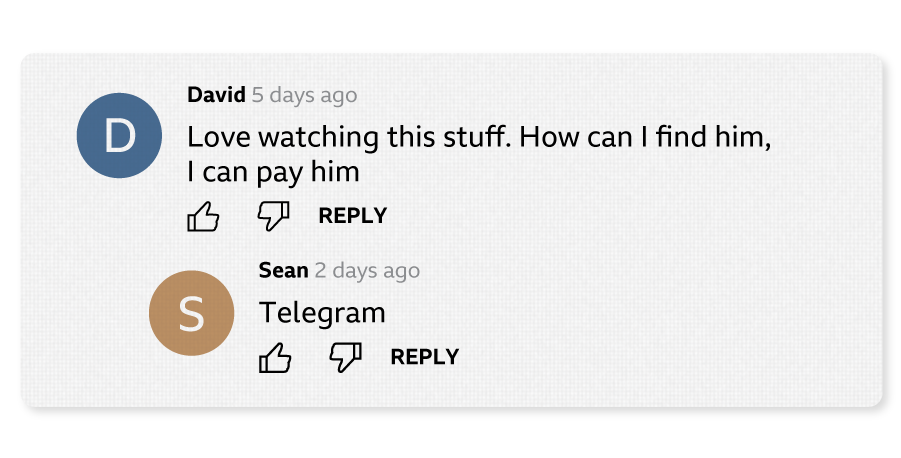

A little over a year ago, the BBC World Service began investigating the emergence of these monkey torture videos too. The videos appeared to be mostly coming out of Indonesia, and being uploaded to YouTube purely for the entertainment of sadists abroad. In the comments under the videos, we found a twisted community of monkey haters who seemed to be getting off on watching baby long-tailed macaques being abused.

Our investigation would lead us to Lucy Kapetanich, to Indonesia and across America and into a hidden world that was darker and more extreme than we could have imagined. The worst of the torture we found there was too depraved to describe in detail in this story, but in her quest to bring it to light, Kapetanich saw it all.

So did Dave Gooptar.

Dave “Yardfish” Gooptar. “I made it my mission to drag these people into the sunlight,” he said (Dylan Quesnel/BBC)

Gooptar lived 4,000 miles away from Kapetanich, in Port of Spain on the Caribbean island of Trinidad. A freelance transcriber by day, he spent some of his free time making video horror movie reviews for his small YouTube channel, called “Yardfish”. He also sometimes watched videos of baby capuchin monkeys on a farm in South Africa, and YouTube’s algorithm went to work on him too.

Gooptar wound up spending four months working on a one-hour video expose, titled “The YouTube Monkey Torture Ring: Part 1”, and in August 2021 he set it live. It didn’t garner a huge number of views. But one of them was Lucy Kapetanich.

Kapetanich had already started her own channel, “Mad Monkey Mayhem”, to try and draw attention to the abuse. When she found Gooptar’s film, she messaged him, and the pair formed a kind of alliance. For now, Kapetanich knew Gooptar only as “Yardfish” and he knew her only as “Mayhem”. Together, they began to dig.

One day, Kapetanich asked Gooptar about a monkey she had noticed appearing in video after video — a baby female. The monkey’s name was listed in the video titles, as though she was some sort of star.

Gooptar already knew who she was, he said.

“Everybody knew who Mini was.”

The first Mini video that Kapetanich saw was tame compared to what came later, but it burrowed into her brain. Mini and two other babies darted frantically around a small bathroom as the man behind the camera grabbed them by their tails and slammed them against the wall. When he did, he let out a high-pitched laugh that haunted Kapetanich. Each slam sickened her more. “The baby monkeys were exhausted and confused,” she said. “And just terrified. They had nowhere to hide.”

Kapetanich found half a dozen other monkeys on the YouTube like Mini. There was Monkey Ji, Baby Ciko, Chiro, Sweetpea, Mona — all baby long-tailed macaques being tortured on film. Some of the monkeys had developed physical tics from the stress. Monkey Ji was known for holding her head in her hands and rocking back and forth. Mini would grip her sides. The monkey haters in the comments loved it. “Abused multiple times a week since a baby. She has lived a TERRIBLE life,” someone wrote, approvingly, under a video of Mini. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen a monkey more broken.”

By that point, hundreds of different YouTube channels were posting videos of baby macaques being abused. In some, the monkeys appeared to die on screen. “Watch them try to breathe while their idiotic brains shut down,” wrote one commenter. Lucy Kapetanich was horrified by what she saw. It hurt to watch as Mini’s owner cooed an Indonesian endearment — “sayang” — to her and then smacked her in the face. It all brought Kapetanich to tears more than once. But the monkey haters loved it.

“He sayang-ed Mini and then immediately smacked her!” wrote one, screen name “Grace”.

“Man I love those videos.”

A few miles away from Lucy Kapetanich in LA, Nina Jackel, a 42-year-old animal rights activist, was also watching this world unfold on YouTube, following a tip off from a fellow activist in the UK. And as Jackel read the comments under the videos, she realised something. The monkey haters were getting frustrated. “They were making suggestions about the types of violence they wanted to see but the video makers weren’t carrying them out,” Jackel explained. “They wanted more extreme violence and they wanted control over the violence.”

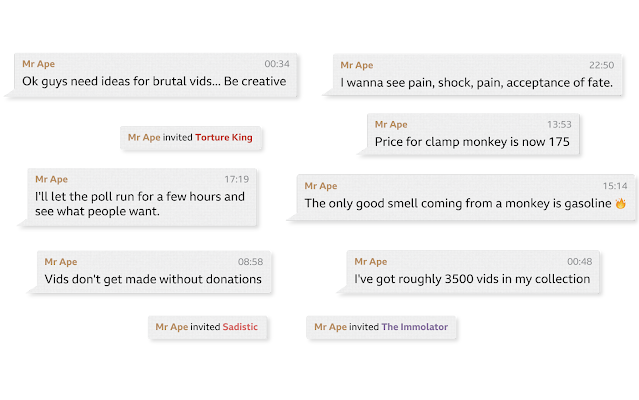

Jackel realised something else, too. There was more extreme violence available. The clues were there on YouTube if you knew what to look for: invitations to join dark web forums or an encrypted messaging app called Telegram. It was on Telegram, in May 2021, that the first big private group began to take shape. The group was called “Million Tears”.

Jackel managed to obtain leaks from Million Tears, and the videos circulating inside — amputations, decapitations, drownings — confirmed that things had taken a leap from YouTube. Jackel put out a press release about the group. It didn’t get a lot of attention, but Lucy Kapetanich and Dave Gooptar saw it, and they got in touch with Jackel to tell her they were looking at these monkey sadists too. The press release spooked the creators of Million Tears into shutting the group down, but almost immediately another Telegram group sprung up in its wake. It was called “Ape’s Cage”.

Animal activist Nina Jackel was sent threats after trying to expose the monkey haters (Joel Gunter/BBC)

Jackel, Kapetanich and Gooptar knew Ape’s Cage existed, but they couldn’t see inside.

Then, on 22 January 2022, an email landed in Lucy Kapetanich’s inbox, from a stranger who called himself “Ronald McDonald”.

“Please keep this between us,” he wrote. “I’m not a bad guy. I’m 48, married to my high school sweetheart, 19 year old daughter, 1 cat and my German shepherd passed away sadly of cancer.”

In the monkey hate community, “Ronald McDonald” was known by his screen name, the “Torture King”. A few months after he first wrote to her, the Torture King sent Kapetanich an email with instructions on how to download Telegram and a link to join Ape’s Cage, and when she did he vouched for her among all the monkey haters inside.

The level of abuse on YouTube, as bad as it had been, had not prepared Kapetanich for the private world of Telegram, where monkeys were known as “tree rats” and no idea for torturing them was too extreme.

Ape’s Cage contained about 400 people. The cast of characters was a mixture of the strange and — even stranger — the seemingly normal, all known to one another by their screen names. There was the Torture King, who had invited Kapetanich in; there was “Sadistic”, a gas station attendant and grandmother in rural Alabama; there was “Bones”, a former US Air Force airman from Texas with a big collection of guns; and “Champei”, who caused chaos and infighting in every group he joined. There was “Trevor”, who couldn’t contribute during daytime hours because, “no phone at work, nuclear stuff”.

And it wasn’t just Americans, there were dedicated members in Europe and Australia. Among the cruellest contributors to the group was “The Immolator”, a 35-year-old woman who loved birds and lived with her parents in the English midlands.

Kapetanich — screen name “Jane Doe” — could hardly comprehend the level of sadism she saw. At the same time, she began messaging privately with the Torture King. She was confused about why he would invite her into this world. He told her that he was ashamed of what he was doing, that he wanted to help her burn the house down from inside. He would be her mole, he said. Soon, they were messaging every day. The Torture King began to reveal his real life to her.

The Torture King at home in Virgina. “It went from baby bottle teasing to fingers being snipped off,” he said (Joel Gunter/BBC)

In real life, he was Mike McCartney, a 48-year-old former motorcycle gang member in Norfolk, Virginia, with a swastika tattoo and a “man cave” in his home decorated with Nazi symbols and Confederate flags. McCartney was well-built, heavily tattooed, and toothless from years of heroin addiction. He had spent two decades in one of America’s most dangerous outlaw motorcycle gangs, before going to prison and dropping out of that life. When the pandemic hit, he started spending a lot of time on YouTube. At some point, he saw his first monkey torture video. It was a video of Mini.

Mini’s owner was “teasing, taking the bottle out of reach”, McCartney said. The video gave him a “good chuckle”. He started watching more, leaving comments. It wasn't long before he got an invitation to a Telegram group.

“They had a poll set up,” McCartney recalled. “Do you want a hammer involved? Do you want pliers involved? Do you want a screwdriver?” He voted and came back to the app later. “And sure as heck there’s a new video with everything that was voted on,” he said. “And it was the most grotesque thing I’ve ever seen.”

McCartney saw a money-making opportunity — downloading torture videos from YouTube and selling them in Ape’s Cage. And as he sold and traded videos he became a trusted member of the monkey hate community, and rose high up in the informal pecking order.

But not to the very top. At the very top of the tree there was only one man. Screen name “Mr Ape”. The Founder and CEO of Ape’s Cage.

No comments:

Post a Comment