Sharp decline in foreign direct investment in Eastern Europe

International investors are increasingly turning their backs on Central, East and Southeast Europe. This is the conclusion of a new report by the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) on foreign direct investment (FDI) made or pledged in the region.

In the first three quarters of this year, the number of greenfield investment projects announced plummeted by 44%, compared to the same period last year. Although the amount pledged for direct investment shrank less sharply, it still fell by a whopping 39%. The number of investment projects announced in the EU member states of the region and the six Western Balkan states also fell by over 40%, compared to the previous year. ‘The crisis in German industry and geopolitical uncertainties are now making their full impact felt on the region,’ explains Olga Pindyuk, Economist at wiiw and author of the report.

In any case, the data show a significant slowdown in new foreign greenfield investment in most countries of the region: only the small Republic of Moldova registered an increase. Among the EU member states, Bulgaria, Poland and Estonia have seen the most swingeing cuts, with commitments halved. In Albania, which is still experiencing a boom due to tourism, the number of greenfield investment projects has plummeted by as much as 88%.

Nevertheless, eight countries recorded a higher inflow of foreign capital than last year. These are led by Estonia, Lithuania and Kosovo. That the investments pledged in Montenegro, Ukraine and Bosnia and Herzegovina shrank faster than the number of projects indicates that the structure of investment is changing in favour of less capital-intensive service projects.

International investors are increasingly turning their backs on Central, East and Southeast Europe. This is the conclusion of a new report by the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw) on foreign direct investment (FDI) made or pledged in the region.

In the first three quarters of this year, the number of greenfield investment projects announced plummeted by 44%, compared to the same period last year. Although the amount pledged for direct investment shrank less sharply, it still fell by a whopping 39%. The number of investment projects announced in the EU member states of the region and the six Western Balkan states also fell by over 40%, compared to the previous year. ‘The crisis in German industry and geopolitical uncertainties are now making their full impact felt on the region,’ explains Olga Pindyuk, Economist at wiiw and author of the report.

In any case, the data show a significant slowdown in new foreign greenfield investment in most countries of the region: only the small Republic of Moldova registered an increase. Among the EU member states, Bulgaria, Poland and Estonia have seen the most swingeing cuts, with commitments halved. In Albania, which is still experiencing a boom due to tourism, the number of greenfield investment projects has plummeted by as much as 88%.

Nevertheless, eight countries recorded a higher inflow of foreign capital than last year. These are led by Estonia, Lithuania and Kosovo. That the investments pledged in Montenegro, Ukraine and Bosnia and Herzegovina shrank faster than the number of projects indicates that the structure of investment is changing in favour of less capital-intensive service projects.

Why Isn’t Europe Diversifying from China?

Over the past seven years, the US and Japan have diversified their trade, sourcing, and investment away from China. The European Union hasn't, despite having derisking policies in place. We explain why.

Agatha Kratz, Camille Boullenois and Jeremy Smith

Download

In the past seven years, the US has actively diversified its trade, sourcing, and investment away from China. Japan, too, is distancing itself from China. The European Union (EU), in contrast, has deepened its trade and investment relationship with China, even as European concerns about economic dependencies grew in the wake of the COVID pandemic and rising geopolitical tensions.

Three factors explain this gap. First, Europe has maintained much greater openness to Chinese clean tech imports in the context of an early and fast-paced green transition agenda. Second, high energy prices in Europe in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have fueled a rise in lower-priced Chinese chemicals imports. Third and finally, the US and Japan have diversified away from China faster in low-tech goods like textiles and furniture. Above all, though, a key difference lies in a lack of European regulatory carrots and sticks of sufficient strength to convince EU companies to rethink their manufacturing and sourcing networks.

No diversification in sight

Since 2017, the US has reduced the share of Chinese products in its overall imports by a stunning 8.4 percentage points (pp), excluding oil and gas (Figure 1).1 It has been replaced by a range of countries, especially Vietnam and Mexico (see “A Diversification Framework for China“). Some of that diversification has relied heavily on Chinese inputs and might even involve a certain degree of transshipped Chinese goods. Yet, the structure of US imports today is markedly different from the past.

Over the same period, Japan also reduced China’s share in its imports, though more gradually, from 29.6% in 2017 to 27.3% in 2023. This was despite a COVID-year rebound that saw most global economies ramp up China-origin imports as Chinese factories remained open for business and produced the goods that the world most needed at scale.

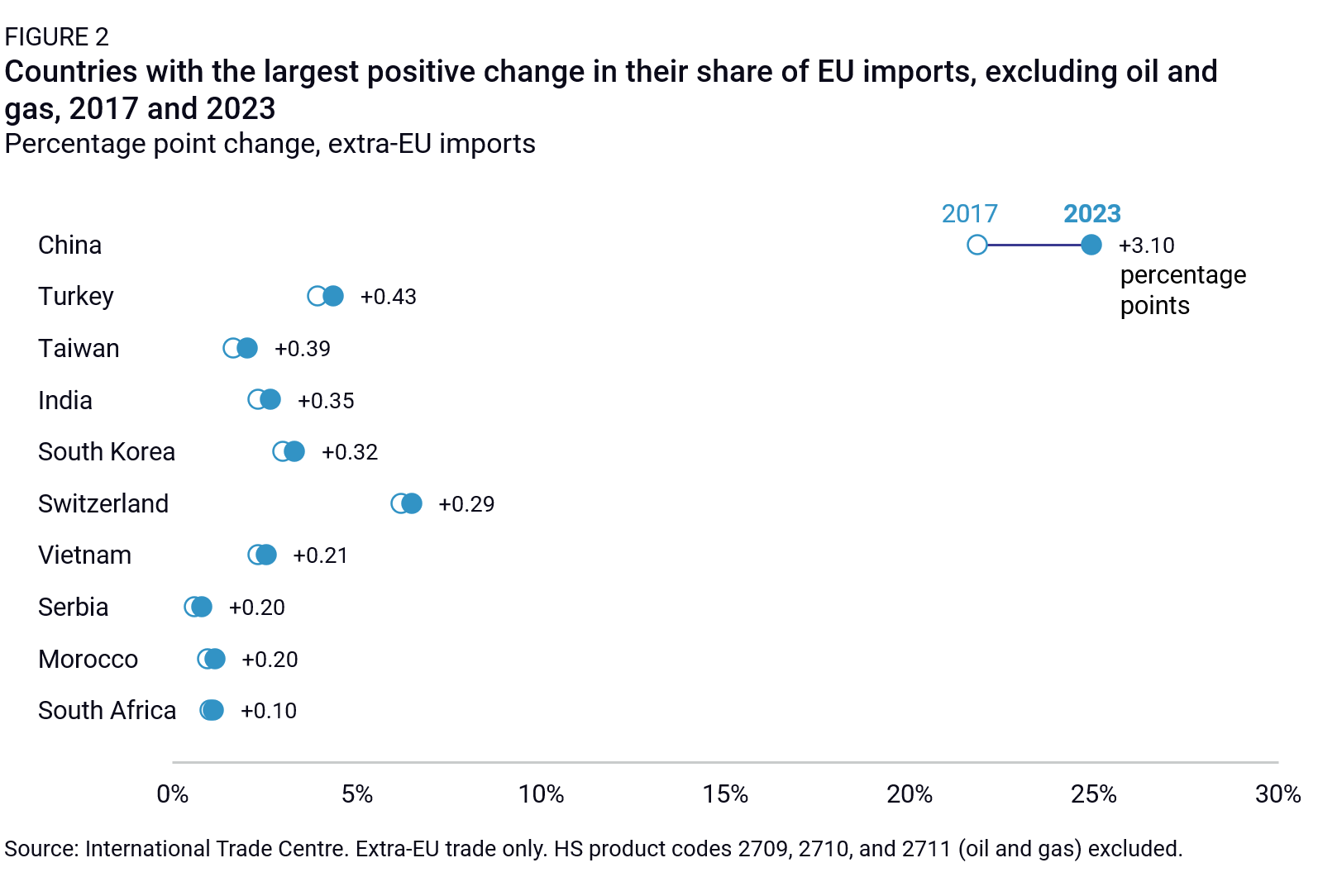

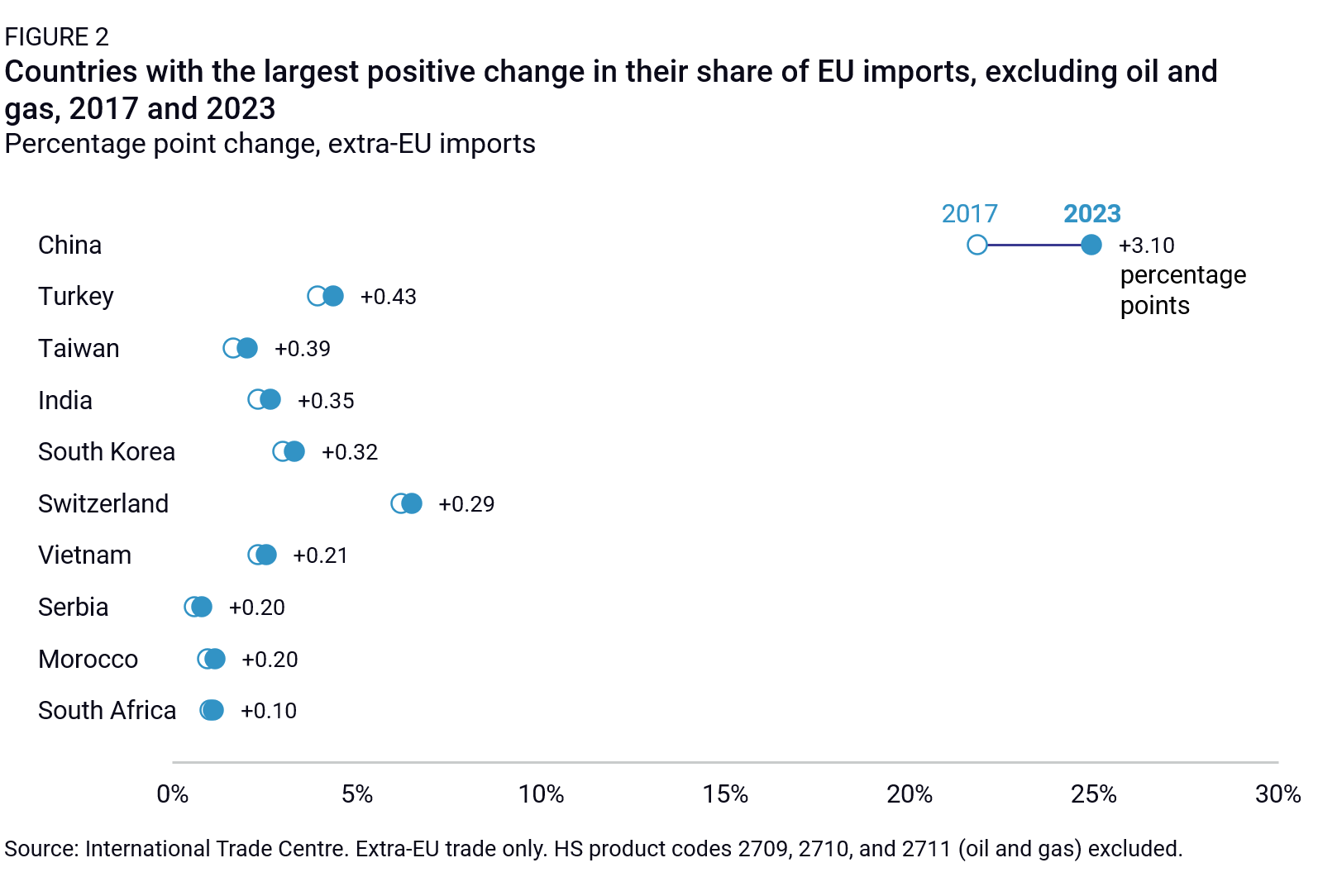

In contrast, China gained more ground in the EU’s import share than any other country between 2017 and 2023 (again, excluding oil and gas, see Figure 2). The trend holds both for imports from countries outside the EU (“extra-EU imports,” + 3.1pp) and when including imports from EU member states (“counting intra-EU,” +1.3pp). No other country aside from China gained even half a percentage point of extra-EU imports over the period. The second and third largest gains came from Turkey and Taiwan, with +0.4pp each. Within the EU, Poland’s share increased the most, by +1.5pp.

The EU is a strange beast, of course. Taken together, European countries are a lot less dependent on China for their imports than the US or Japan because they trade significant amounts between themselves—as would US states or Chinese provinces. However, looking at the EU as a whole and considering trade with non-EU partners, we see that the EU’s dependence on China for imports has increased over the past five years, rising from 22% in 2017 to a peak of near 27% in 2022, and then leveling off to 25% in 2023. In 2019, EU import reliance on China overtook that of the US—as China imports came under broad US tariffs—and has since become gradually closer to levels seen in Japan or South Korea, two economies highly intertwined with neighboring China.

OECD Trade in Value Added (TiVA) data shows a similar trend (Figure 3). The EU’s dependence on Chinese value-added for final demand increased from 13.6% in 2017 to 17.3% in 2020, quickly approaching US levels. The US, in contrast, saw its reliance on Chinese value-added remain roughly stable during the 2015-2020 period. By 2020, Japan and South Korea still showed a much stronger reliance on Chinese value-added than both the EU and the US, but South Korea saw the fastest increase (+5.4pp).

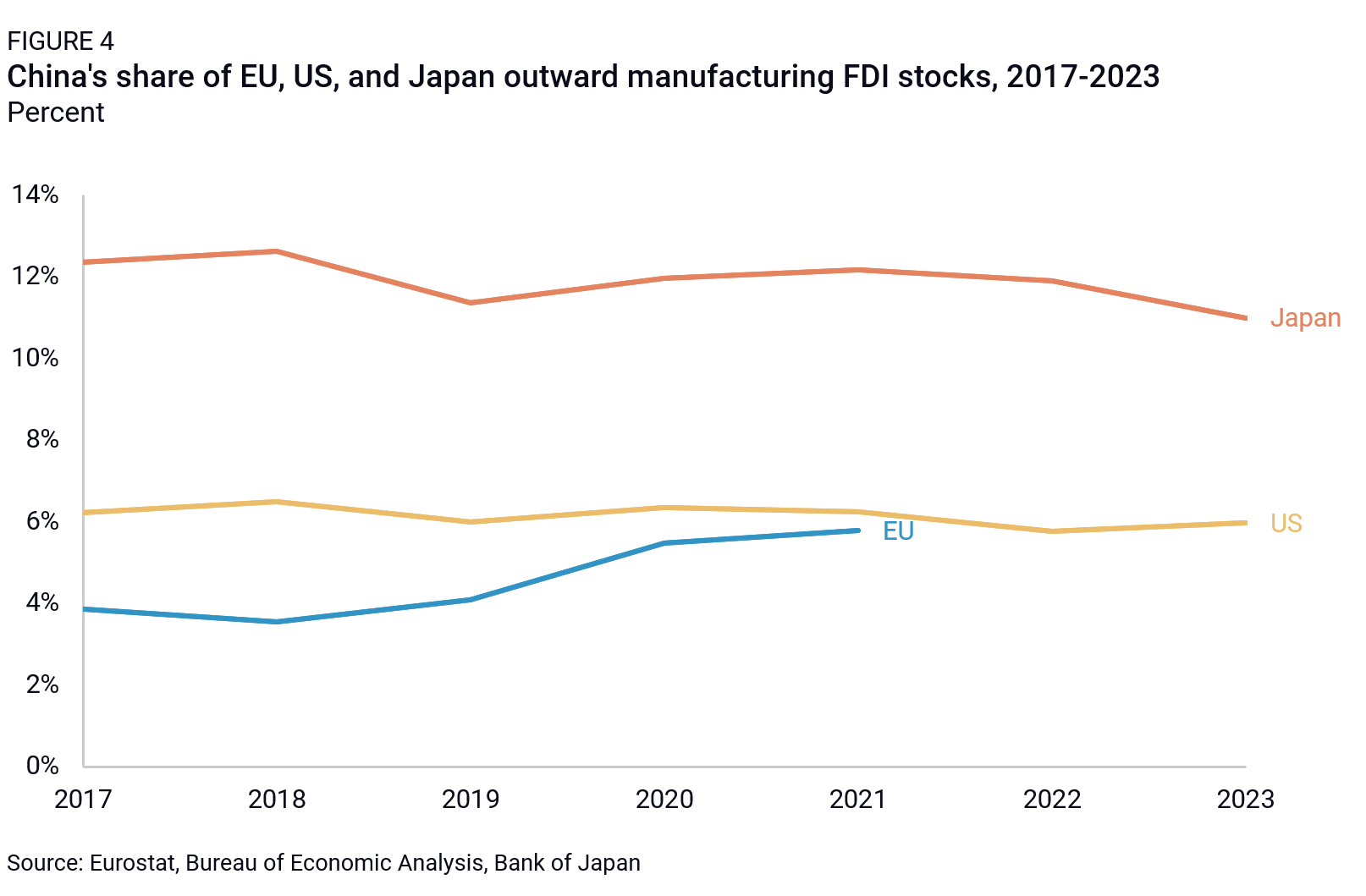

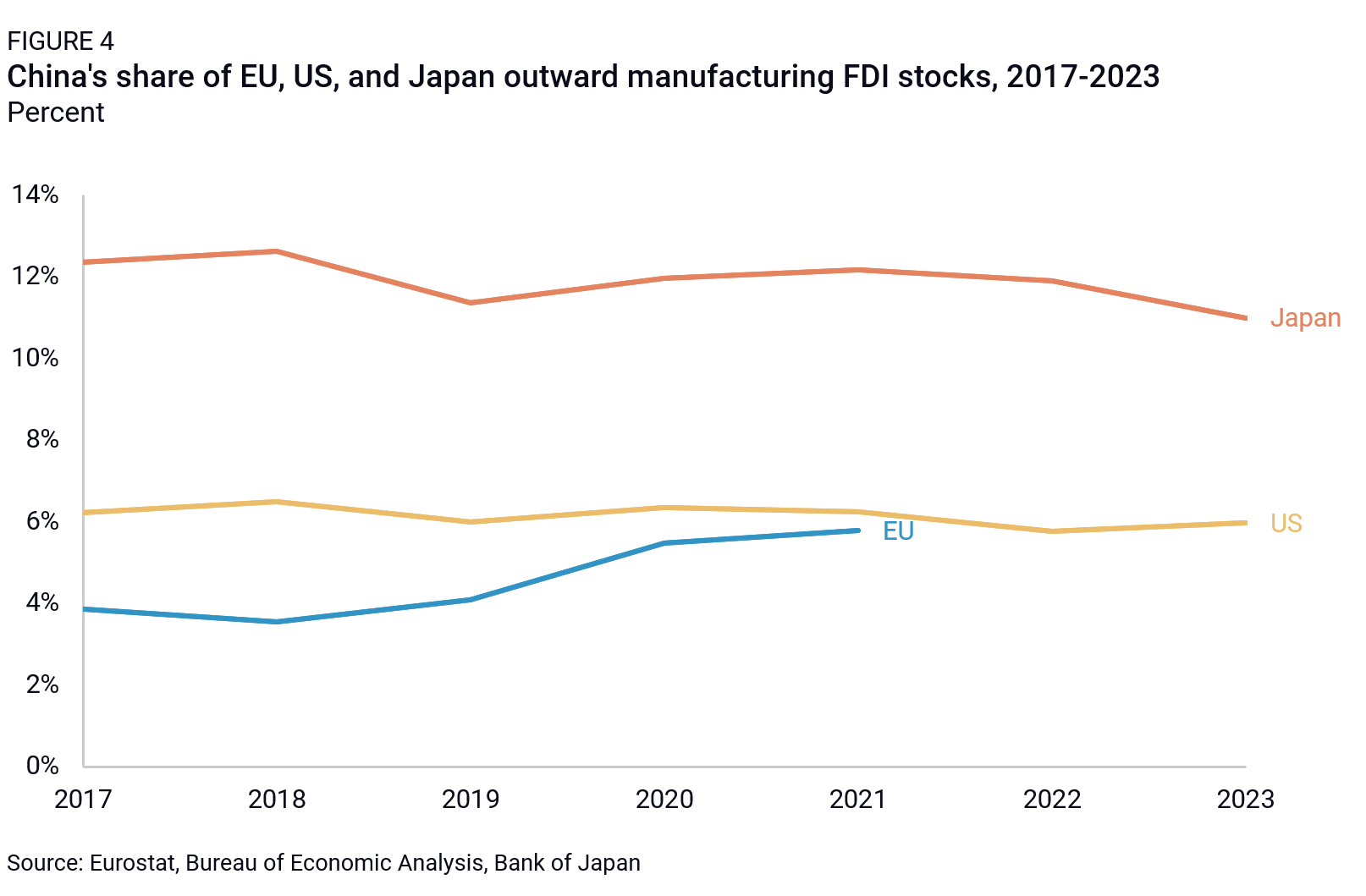

Finally, China’s share of the EU’s outward manufacturing FDI stocks rose by 2pp from 2017 to 2021, albeit from a relatively low base of 4% (Figure 4). EU statistical delays obscure the picture somewhat, but more up-to-date Rhodium Group data suggest that EU manufacturing FDI has continued to flow into China since 2021, with a record high in EU greenfield FDI registered in Q2 2024. Meanwhile, over the past several years, China’s share of manufacturing FDI stocks has declined slowly for the US (-0.2pp) and fast for Japan (-1.3pp).

In short, the EU has seen China’s share of its imports, value-add, and investment increase over the past six years, in contrast to the US and Japan, which have decreased their China exposure on most or all fronts. Of course, aggregate import reliance does not equal critical input dependency—arguably the more substantial type of exposure—but it shows how Europe has been at odds with a broader trend in Japan and especially in the US.

Recent analysis by the Peterson Institute for International Economics reinforces this view, showing that while US sourcing of manufactured goods has substantially diversified away from China over the past five years, EU manufacturing imports have only become more concentrated in the aggregate—a pattern that holds for both low- and high-tech products. A deeper historical analysis by MERICS, focusing on critical EU import dependencies on China, also emphasizes the EU’s dramatically increased exposure to Chinese imports over the past 20 years, particularly in electronics. A separate Oxford Economics study acknowledges that the US and Japan have lowered their share of intermediate goods imports from China while the dependence of European economies has notably increased.

Explaining the differences

These findings beg the question: given that the EU, the US, and Japan are all pursuing efforts to reduce their economic dependencies and diversify their trade patterns, especially from China, what explains the EU’s increasing rather than decreasing trade, value-add, and investment exposure to China in recent years?

A China-powered green transition

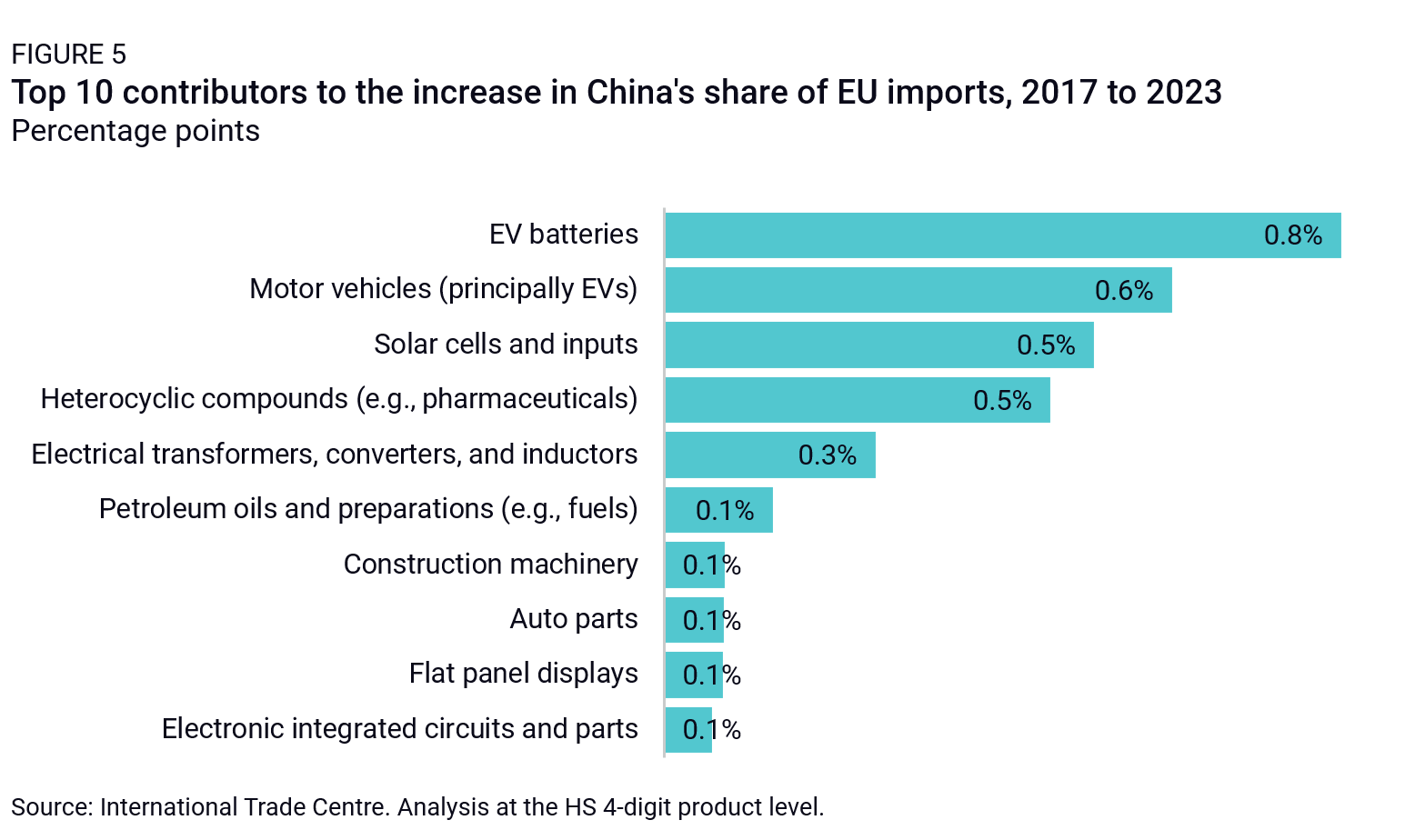

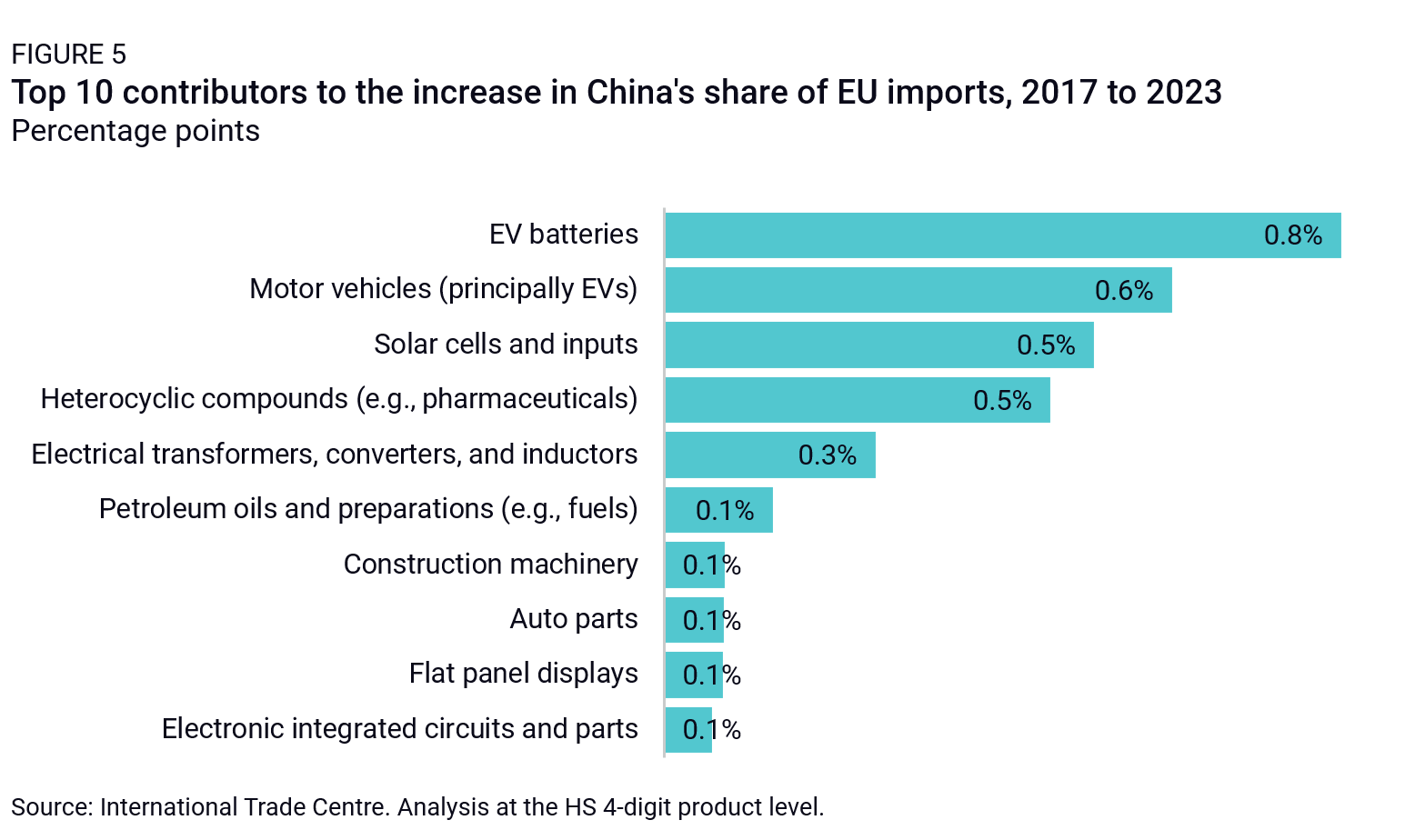

A first way to explain this gap is to identify the product categories where the EU’s reliance on China has increased the most since 2017, the year before the US imposed its first round of Trump tariffs on China (Figure 5).

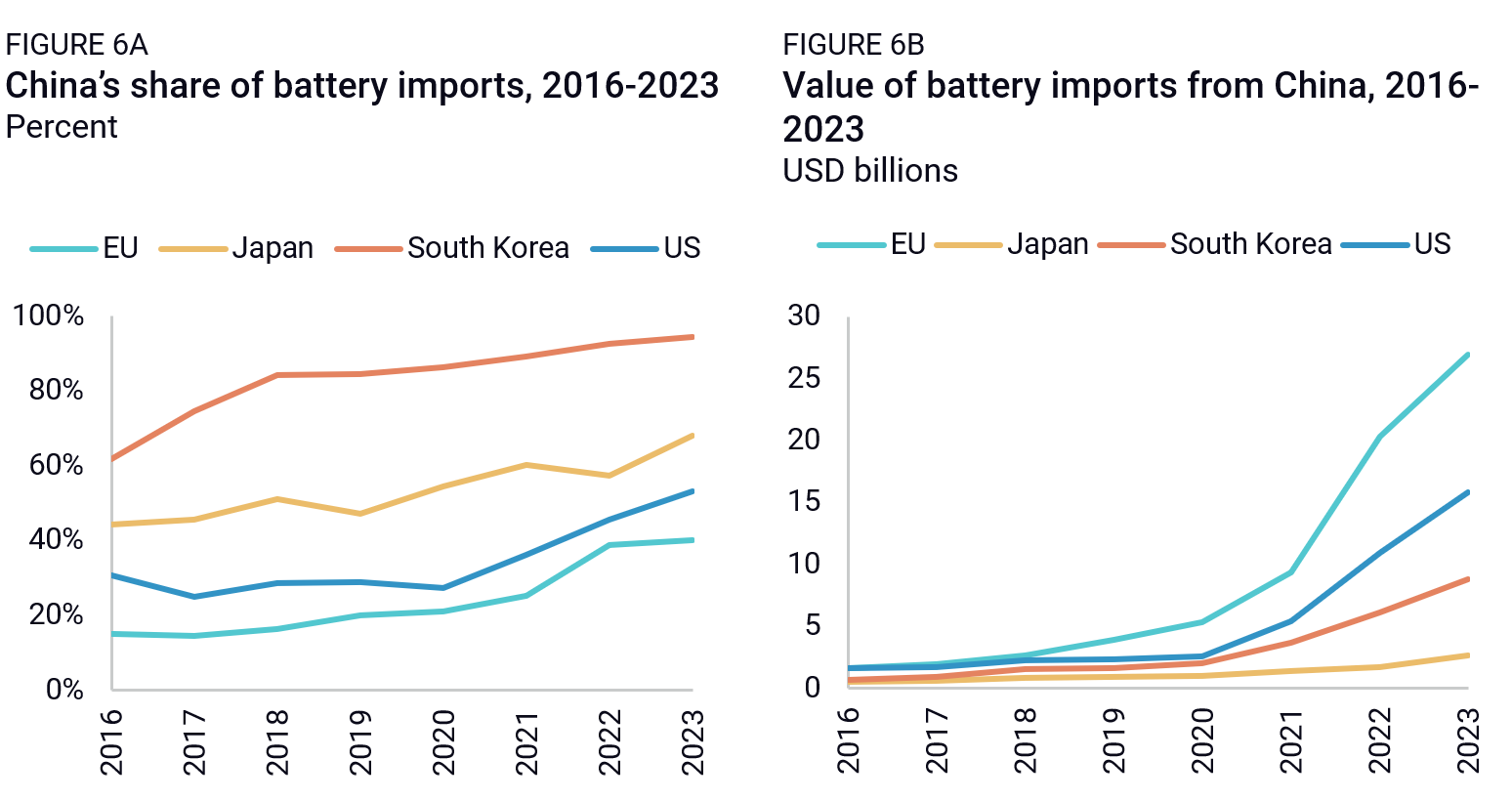

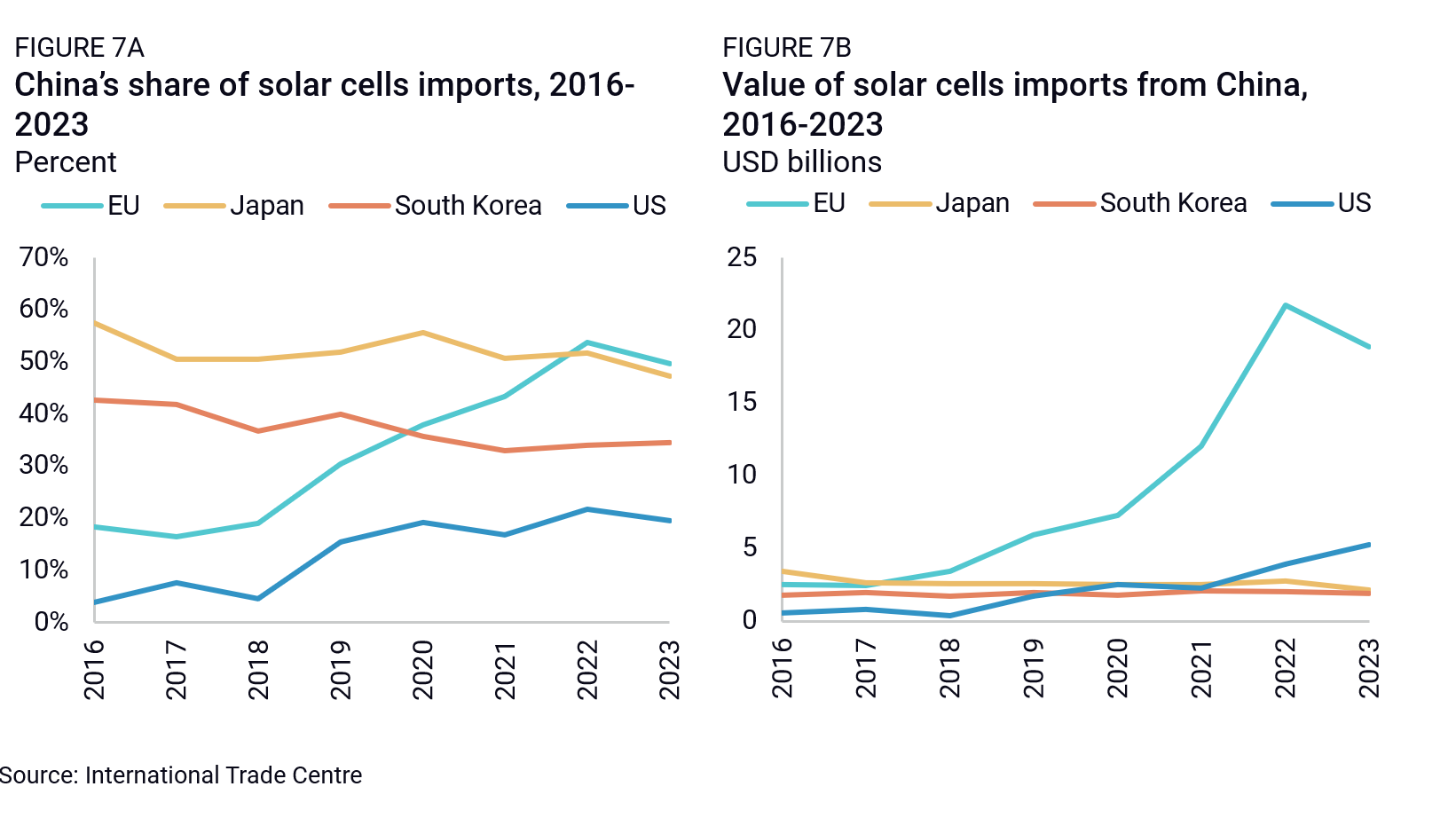

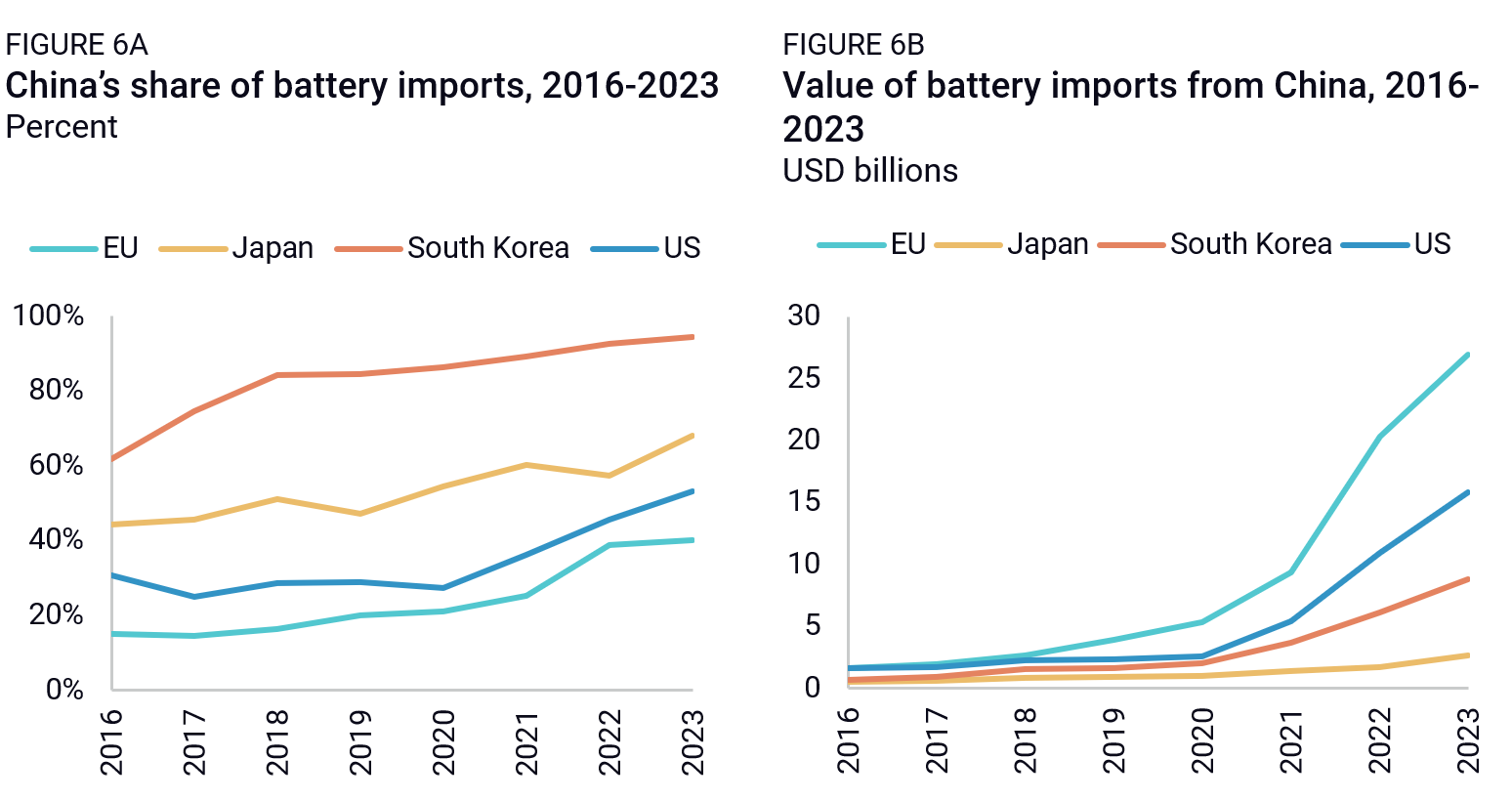

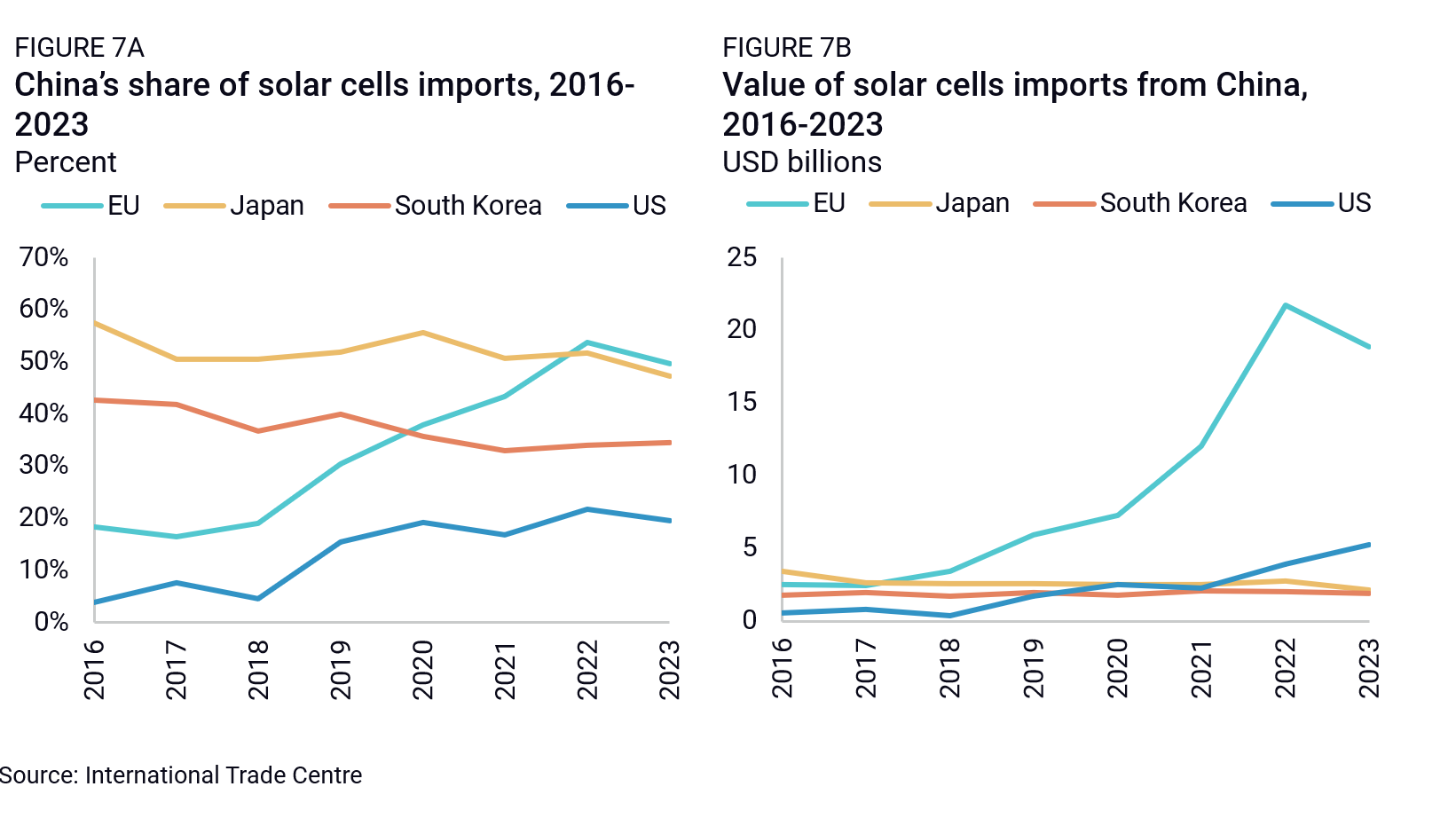

Batteries and electric vehicles (EVs) contributed over a third of the increase in China’s share of EU imports, reflecting China’s growing competitiveness in both fields and increasing dominance of the global EV supply chain. In fact, China’s share of battery imports increased across the EU, US, and Japan (Figure 6A), but the value increase in Europe was much greater (Figure 6B). The same is true of solar cells. Both the US and the EU registered increases in the absolute and relative value of China-origin imports, but for the EU, this happened on a completely different scale (Figure 7A and 7B).

The fact that Europe was an early mover in rolling out policies to support the green transition probably explains some of this disconnect. In batteries, the EU lacked credible domestic competitors (unlike Japan or South Korea) or an industrial policy that attracted such producers onshore (as in the US). More broadly, this reflects Europe’s greater openness to Chinese clean tech imports over the period. By contrast, tariffs and provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) made it harder and/or costlier for Chinese clean tech manufacturers to export to the US.

An energy crisis

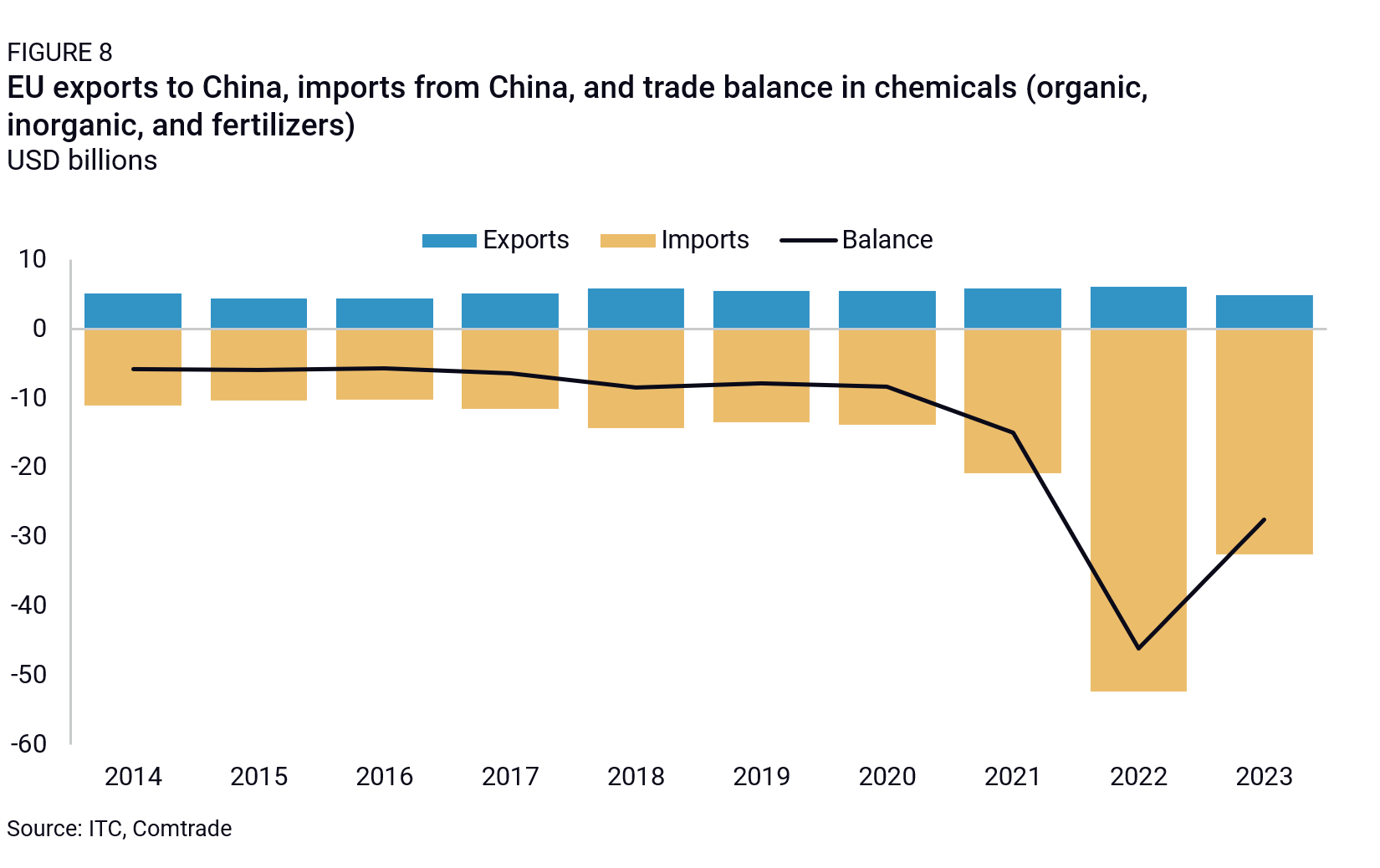

Another explanation for Europe’s growing entanglement with China is the energy crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In recent years, China’s share of EU imports increased quickly and significantly in chemicals—especially organic compounds used in pharmaceuticals—and fuels such as jet fuel and kerosene. Rising energy costs in Europe made importing these chemicals from China—instead of producing them at home—much more attractive. At the same time, rapid production capacity growth in China pushed down Chinese chemicals prices and facilitated export market share gains. Together, these two factors worsened the EU’s trade deficit with China, with key EU chemicals imports more than doubling from 2020 to 2023 (Figure 8). The shift is already triggering EU reactions. Over the past year, Brussels has opened a series of trade defense cases against Chinese exports of chemicals used in food products, cosmetics, and cleaning products, all on the back of industry complaints.

No tariff shock

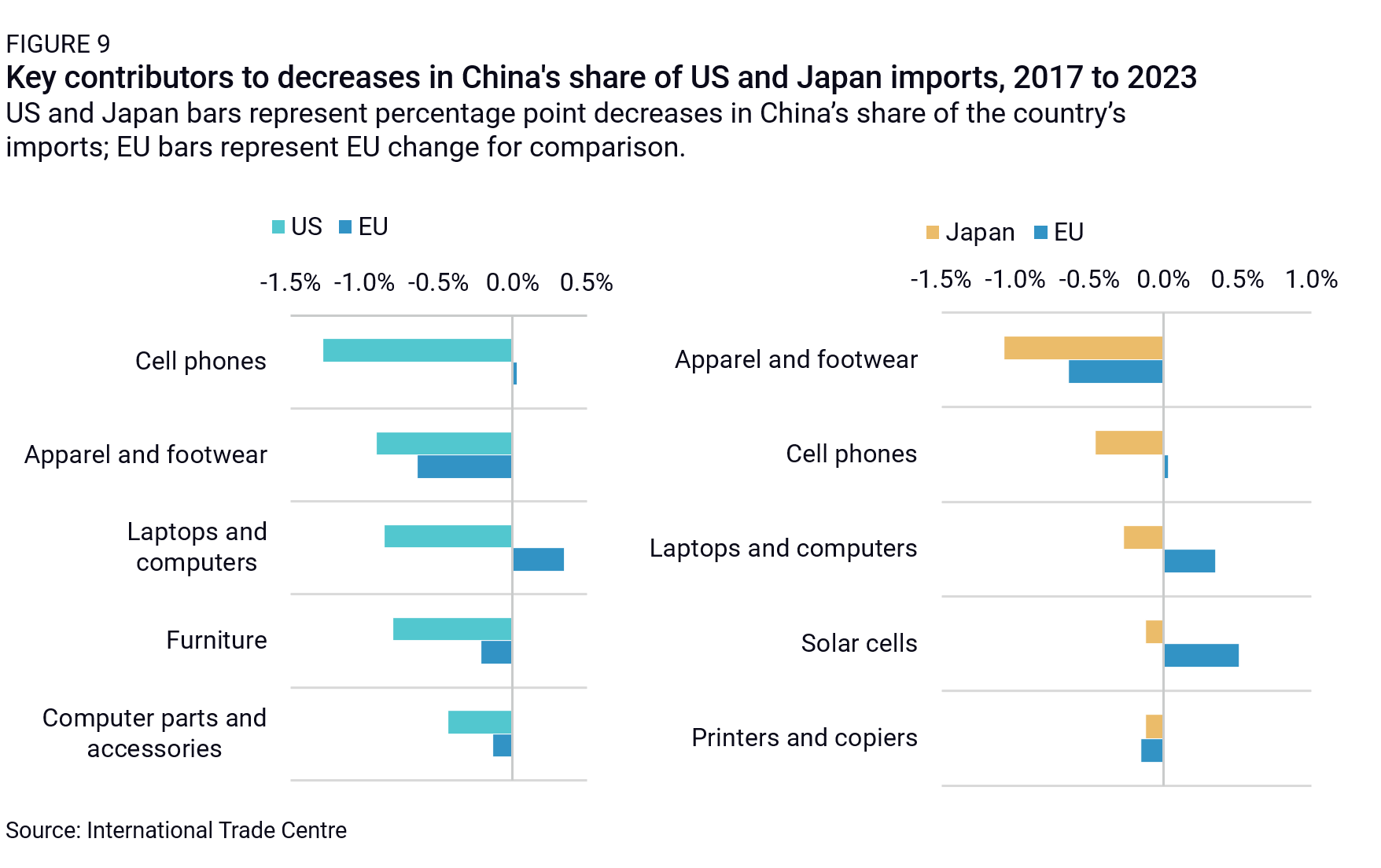

Another way to look at the question is to explore which areas saw significant diversification from the US and Japan but not from the EU (Figure 9). Some of the largest contributors to US and Japanese diversification are labor-intensive, low-value-added sectors such as apparel, footwear, and furniture. In these categories, China’s high global export share began a gradual, structural decline even before the trade war, as it started undergoing a process of “graduation” to higher-tech activities. Although the EU has shifted its sourcing somewhat—to many of the same markets as the US and Japan, including Vietnam and Bangladesh—it has not done so nearly as quickly. The US and Japan have also quickly diversified their consumer electronics imports since 2017. Yet, here again, China’s share of EU imports has either hardly budged (computer parts, cell phones) or increased (laptops, solar cells).

It is worth noting that these sectors are often perceived as less strategic than others, like green tech or specialty chemicals. It is unclear that the EU is even seeking to de-risk from China in these areas. Yet they did contribute to the US and Japan’s import diversification over the past half-decade or so, and hence, they explain part of the gap with Europe.

Policy choices likely explain much of the difference. Starting in 2018, US tariffs on a range of consumer goods imports from China, including some textiles, furniture, and consumer electronics, have redirected production and assembly from China to third countries like Mexico, Vietnam, and Bangladesh. Japan’s subsidy schemes, strong political signaling to domestic firms to diversify production and sourcing away from China, and greater historical footprint in Southeast Asia might have impacted diversification progress, too.

Re-shoring vs. near-shoring

Focusing on trade, lastly, underestimates the fact that China gained important ground while Europe also started producing more domestically. In fact, the jump in China’s share of EU imports is much greater for extra-EU imports (+3pp) than imports including intra-EU trade (just +1pp). This difference indicates that EU member states have quickly picked up market share from non-EU importers. US trade diversification happened largely thanks to external players, including Mexico, Vietnam, and Taiwan. But in sectors like semiconductors, massive new investments in the US also suggest diversification is or will be happening through a ramp-up of local production.

In Europe, some degree of diversification is similarly happening on the back of production increases in select EU member states—including and especially Central and Eastern European economies, who share some of the manufacturing appeal of ASEAN or Mexico. In the battery sector, for example, Poland, Hungary, and Czechia have emerged as significant players, increasing their share of total EU battery imports from 7% in 2017 to 35% in 2023. While this does not negate the fact that the EU’s import dependency on China increased over the past five years, it indicates greater “friendshoring” activity than topline trade numbers indicate.

EU policies: More bark than bite

Could structural differences between the US and EU economies, finally, help explain some of the observed differences? What if Europe were intrinsically more dependent on global trade than the US? Or what if the US was significantly more service-oriented than Europe? A closer look shows that both economies have, instead, similar levels of manufacturing output as a share of GDP, a comparable degree of reliance on intermediate input imports in their manufacturing sectors, and a similar level of imports as a share of their overall economy. Both economies are major markets for (and importers of) autos, batteries, solar PV, and chemicals.

This leads us to the conclusion that the variation in results is due to policy differences between the EU and the US between 2017 and 2023. On the surface, both EU and US policymakers have adopted diversification as an overarching policy principle—especially as the COVID pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine underlined the risks of excessively concentrated supply chains or supply sources. Both EU and US officials have raised specific concerns over excessive exposure to Chinese imports, especially to certain China-made critical inputs. Yet policy reactions have been very different. For one, the US took action several years before the EU. The first major wave of US tariffs against China was rolled out by the Trump administration in 2018, years before the EU started using its defensive toolbox in full or defining “de-risking” as a policy objective. Also, US policies, including export controls, industrial policy support, and ICTS measures, have involved a much more robust set of carrots and sticks than their European equivalents (Table 1).

Trump-era tariffs are an obvious example. They brought the effective tariff rate on Chinese imports to the US to around 11-12% and affected about two-thirds of Chinese exports to the US before a series of exemptions were introduced. In contrast, the EU’s largest case to date, on China-made EVs, covers about 2% of China’s exports to the EU.

Consider major state support programs. Both the EU and the US have launched major sectoral and decarbonization support schemes in recent years. Yet US initiatives have come with stringent, binding conditions and guardrails meant to encourage diversification of related supply chains away from China. In contrast, the EU’s main regulatory framework for critical raw materials and cleantech diversification, the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) and Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA) offer non-binding targets for EU’s manufacturing of clean technologies and extraction, processing, refining, and recycling of raw materials.

Finally, in certain sectors, the US is simply choosing to ban some Chinese goods and technologies in ways that will fully reshape US-bound supply chains—as is the case with the latest ICTS rules on Chinese and Russian connected vehicles.

This is in addition to an intense and bipartisan US regulatory agenda on China and a highly China-skeptical political environment, both of which are sending clear and credible signals to US companies that they need to diversify now or face costly consequences. The draft BIOSECURE Act is a potent example. This bill would prohibit US federal agencies from procuring or obtaining biotechnology equipment or services from certain “biotechnology companies of concern” (currently, five Chinese biotech firms) or contracting with any entity that uses such equipment in the performance of federal contracts. While the act has yet to be passed by Congress and signed into law, it has already created a powerful enough signal that some US companies are reconsidering their ties to Chinese biotech firms. In October 2024, Wuxi AppTec, one of the listed firms, was reportedly considering the sale of some US laboratories and manufacturing plants in response to growing regulatory pressures.

Japan presents another successful example of policy-driven diversification, focused mainly on encouraging companies to de-risk through positive incentives. Like the EU, Japan’s de-risking programs do not explicitly target China, but many Japanese firms have dubbed these government incentives as a “China exit subsidy.” Programs such as the Program for Strengthening Supply Chains and the Program for Promoting Investment in Japan to Strengthen Supply Chains provided substantial financial support to firms reshoring their operations to Japan or relocating production to other Southeast Asian countries. Japan’s subsidies to attract investment in key sectors such as semiconductors and electric vehicles also far exceed EU funding. Overall, Japan is expected to disburse about $65 billion in subsidies to support the semiconductor industry by 2030, compared to $57 billion in the US and only about $9 billion in the EU.2

Outlook: What about the next five years?

In 2023, China’s share of EU imports (excluding oil and gas) was down almost two percentage points from its 2022 peak. The question is whether this signals a longer-term shift or just a short-term correction after particularly high Chinese export prices in 2022.

In the short run, we think the EU’s dependency on Chinese imports is likely to deepen further. China’s economic weakness will perpetuate the gap between consumption and production and compound the urge to grow exports as a lever of growth. As a major global market, the EU will be on the receiving end of these flows. Trump’s decision to impose further tariffs on China will likely accentuate the trend. The first iteration of “Trump tariffs” had a significant impact on US-China trade flows and global supply chains more broadly. On the 2024 campaign trail, Trump promised to slap 60% tariffs on Chinese exports to the US. Whether or not these are implemented in full and at these levels, additional US tariffs will end up redirecting some Chinese exports to Europe. China’s responses, which will likely involve significant RMB depreciation, will further amplify the trend and significantly increase the cost of diversifying manufacturing or sourcing to other emerging markets.

Because Brussels is already concerned about Chinese overcapacity and a potential influx of low-price Chinese products, it is unlikely to sit idle, of course. We would expect the Commission to launch its own series of trade defense cases. These could involve more drastic measures like safeguards, already used to shelter Europe from the effects of US tariffs in 2018. Yet because Brussels is still intent on using WTO-compliant tools, at least in the short run, and because these necessitate a sectoral focus, EU officials will need to prioritize their defensive efforts. Primacy will likely be given to large value-add and job contributors, like chemicals, machinery, or select clean tech equipment—in addition to EVs, which are already in focus. Sectors where the EU does not have as much of a local industrial base—such as textiles, furniture, and electronics—will likely remain open and see a rise in Chinese imports. Because exporting hubs like Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Thailand will redirect production capacity to serve the US, Europe’s needs might end up being addressed, even more so than in the past, through China-based capacity.

In the long run, Europe might shift back to diversification. Product categories that have seen major upticks in Chinese import exposure over the past five years could progressively become the target of more defensive action from Brussels. Given the EU’s dependency on China for solar PV supply, it is unlikely that the Commission would launch a major trade defense case for solar. Brussels, however, already launched an ex-officio FSR case against Chinese firms active in Europe’s wind sector. If European battery champions continue to face financial difficulties, the Commission could consider additional action on battery imports—if just to foster greater investment on the ground in Europe. These actions, and possibly more, would constrain Chinese firms’ EU market share, including through exports.

Beyond trade and subsidies cases, Europe might also start using more stringent regulations and public procurement criteria to force a diversification of vendors away from China. Lithuania and the Netherlands have already introduced laws that bar certain Chinese technologies and products in wind and solar projects on cybersecurity grounds. The NZIA and CRMA allow resilience criteria in public auctions, which could de facto limit Chinese supplier access to a range of publicly procured contracts in Europe. The EU is currently revising its public subsidies rule to similar effect. Finally, certain member states like France are introducing their own standards-based criteria for access to certain public funding schemes—namely environmental standards-based tax credits for EV purchases—in ways that make Chinese imports less competitive.

In short, measures from member states are likely to further restrict Chinese firms’ access to the EU market. These moves will probably persist even as member states seek to hedge against Trump through greater China outreach. They could even be fast-tracked if further evidence emerges of the cyber and resilience risks attached to using Chinese goods, technologies, or systems, such as evidence of Chinese firms sending sensitive data back to China or Beijing, significantly restricting access to certain critical inputs or raw materials.

Positive inducements to diversify European manufacturing and sourcing at scale have been harder to deploy for the EU, but they are not out of the question. European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen’s political guidelines include pledges for pan-EU funding for key areas of European competitiveness, and certain member states like France have long argued for more forceful financial support to European industry and innovation. Germany and a few other member states will prove major obstacles, but increasing pressures from the US and China could drive a step change in approach.

Finally, US regulatory bans on certain Chinese goods and inputs, like the new ICTS rule (see October 8, “Car Trouble”), will create incentives for European firms to diversify their supply chains away from China faster than they have so far.

In that context, EU diversification could pick up on the back of US, Japanese, and Chinese diversification. As investment continues to flow to ASEAN and other “alt China” destinations, non-China production capacity will expand in ways that will make it much easier for European firms to procure or manufacture outside of China in the long run.

Key outcomes of the meeting included agreements on bilateral trade, investment cooperation, and agricultural exports. These agreements aim to strengthen economic ties between China and Poland, which could have significant implications for the business communities in both countries as well as in Europe. During the meeting President Xi also announced that China will remove the visa requirement for Polish citizens, allowing them to enter the country without a visa for stays of up to 15 days. The new policy is expected to facilitate easier travel for Polish tourists and businesspeople, thereby promoting cultural exchange and economic cooperation between the two nations.

In the context of increasing tensions between China and the EU—particularly over proposed tariffs on electric vehicles and China’s investigation into EU pork imports—the Sino-Polish dialogue stands out as a beacon of potential stability and cooperation. President Duda’s remarks on the mutual respect and strong political relationship between Poland and China over the past 75 years highlight a foundation for continued positive engagement.

The launch of a new freight train service from Guangzhou to Warsaw further underscores the commitment to improving trade efficiency. This service, which reduces transit time by 30 percent, is expected to enhance the flow of goods such as air conditioners and coffee machine accessories, benefiting businesses on both sides. This development is particularly significant for the Polish business community, which stands to gain from quicker and more reliable access to Chinese markets.

June 23, 2024 – China and the EU are set to have more talks regarding EV tariffs

China has agreed to enter discussions with the EU regarding the imposition of higher tariffs on Chinese EVs. This decision was announced during the visit of Germany’s Vice-Chancellor and Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, Robert Habeck, to Beijing. Habeck welcomed this move as a positive first step, though he noted that further actions would be necessary.

The talks aim to address the EU’s anti-subsidy investigation launched last year, which led to the decision to increase tariffs on Chinese EVs up to 48 percent. The agreement to begin consultations follows a video conference between China’s Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao and EU Executive Vice-President and Trade Commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis.

Germany, heavily reliant on the Chinese market for its carmaking industry, has been critical of the EU’s tariff decision. Habeck’s visit marks the first by a senior European politician since the new duties were announced. The Chinese market’s significance for German carmakers makes Berlin particularly vulnerable to any potential retaliatory measures from the Chinese government, which has already initiated an anti-dumping investigation into EU pork products.

June 13 to June 15, 2024 – G7 reunites in Italy and issues warning to China, escalating trade tensions

During the G7 summit held in Apulia, Italy, leaders issued a strong warning to China over its trade practices, highlighting concerns such as “harmful overcapacity” and “market distortions.” While emphasizing that their aim is not to harm China, they expressed reservations about its industrial policies and non-market practices. Additionally, the G7 leaders condemned China’s support for Russia, particularly the transfer of dual-use materials that could aid Russia’s defense sector, and pledged to take measures against entities in China and third countries that support Russia’s military efforts. This follows the European Commission’s announcement of import duties on Chinese EVs, further escalating trade tensions.

In response, the Chinese government accused the G7 nations of “smearing and attacking” China, with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs asserting that these actions hinder international peace and regional stability. China summoned Japan’s ambassador to protest the “hype around China-related issues” and warned the UK to stop its “slander” to avoid damaging bilateral relations.

June 12, 2024 – The European Commission announces provisional import tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles

On June 12, the European Commission announced provisional import tariffs on electric vehicles (EVs) from China, ranging from 27.4 percent to 48.1 percent, following an anti-subsidy investigation. This decision comes shortly after the United States imposed their own tariffs on Chinese EVs, which have risen to an unprecedented 102.5 percent.

In response, the Chinese government has initiated an anti-dumping investigation into pork imports from the EU. While the Chinese Ministry of Commerce did not directly link this investigation to the EV tariffs, it is widely perceived as a retaliatory move. The investigation encompasses various pork products, including fresh and frozen meat, intestines, and other internal organs, and is expected to last one year with a possible six-month extension.

This strategic decision is deemed to mainly target European agriculture rather than German automakers, possibly to leverage in trade negotiations. Despite speculation that China might impose a 25 percent duty on large-engine gasoline-powered vehicles, which would significantly impact brands like Mercedes and BMW, the government has refrained from this action, likely considering the significant presence of these automakers in China and their opposition to the EU tariffs.

Meanwhile, the European Commission’s trade measures may extend beyond EVs to other key components of Europe’s energy transition. Recently, an anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese solar panel manufacturers was closed after the companies withdrew from a public project in Romania. Additionally, an ongoing investigation into Chinese wind turbine suppliers is being conducted under the new Foreign Subsidies Regulation.

June 6 to June 9, 2024 – The European Parliament elections reveal a shift to the right

The 2024 EU elections, held between June 6 and June 9, 2024, have significantly reshaped the political landscape within the EU, prompting a re-evaluation of power dynamics among member states and within the European Parliament. Despite varying interpretations of the results, two primary perspectives have emerged: a notable surge in far-right support and a resilient centrist presence, particularly from mid-sized and smaller countries.

In Germany and France, the far-right experienced significant gains, with dramatic increases in voter support. However, centrist parties have maintained a stronghold at the EU level, largely due to voters from countries like Poland, Spain, and Romania. This has enabled a pro-European, centrist majority to form, likely securing Ursula von der Leyen another term as Commission president. This majority will not be heavily influenced by the governing parties of France and Germany, thereby diminishing the influence of leaders like Emmanuel Macron and Olaf Scholz within the European Parliament.

Macron’s party secured only 13 of the 79 seats in the Renew Europe group, while Scholz’s Social Democrats won just 14 seats in the 135-member S&D group. In contrast, other leaders have emerged stronger, such as Donald Tusk of Poland’s Civic Coalition, which won 21 seats, and Romania’s coalition parties, which secured 19 seats. These developments suggest that countries previously considered on the periphery will now be central to the new von der Leyen majority, impacting decisions on the Commission president, commissioners, regulations, and the general direction of the EU.

As EU leaders convene at various international summits, such as the G7 meeting in Italy and the upcoming Ukraine Peace Summit in Switzerland, discussions about top EU jobs are taking place alongside broader international issues. The emerging consensus points toward von der Leyen continuing as Commission president, Roberta Metsola staying on as European Parliament president, and António Costa as a potential European Council president. Estonia’s Kaja Kallas is also a contender for the EU foreign policy chief position.

This timeline was first published on June 21, 2024, and will show rolling updates.

Why Isn’t Europe Diversifying from China?

Over the past seven years, the US and Japan have diversified their trade, sourcing, and investment away from China. The European Union hasn't, despite having derisking policies in place. We explain why.

Agatha Kratz, Camille Boullenois and Jeremy Smith

Download

In the past seven years, the US has actively diversified its trade, sourcing, and investment away from China. Japan, too, is distancing itself from China. The European Union (EU), in contrast, has deepened its trade and investment relationship with China, even as European concerns about economic dependencies grew in the wake of the COVID pandemic and rising geopolitical tensions.

Three factors explain this gap. First, Europe has maintained much greater openness to Chinese clean tech imports in the context of an early and fast-paced green transition agenda. Second, high energy prices in Europe in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have fueled a rise in lower-priced Chinese chemicals imports. Third and finally, the US and Japan have diversified away from China faster in low-tech goods like textiles and furniture. Above all, though, a key difference lies in a lack of European regulatory carrots and sticks of sufficient strength to convince EU companies to rethink their manufacturing and sourcing networks.

No diversification in sight

Since 2017, the US has reduced the share of Chinese products in its overall imports by a stunning 8.4 percentage points (pp), excluding oil and gas (Figure 1).1 It has been replaced by a range of countries, especially Vietnam and Mexico (see “A Diversification Framework for China“). Some of that diversification has relied heavily on Chinese inputs and might even involve a certain degree of transshipped Chinese goods. Yet, the structure of US imports today is markedly different from the past.

Over the same period, Japan also reduced China’s share in its imports, though more gradually, from 29.6% in 2017 to 27.3% in 2023. This was despite a COVID-year rebound that saw most global economies ramp up China-origin imports as Chinese factories remained open for business and produced the goods that the world most needed at scale.

In contrast, China gained more ground in the EU’s import share than any other country between 2017 and 2023 (again, excluding oil and gas, see Figure 2). The trend holds both for imports from countries outside the EU (“extra-EU imports,” + 3.1pp) and when including imports from EU member states (“counting intra-EU,” +1.3pp). No other country aside from China gained even half a percentage point of extra-EU imports over the period. The second and third largest gains came from Turkey and Taiwan, with +0.4pp each. Within the EU, Poland’s share increased the most, by +1.5pp.

The EU is a strange beast, of course. Taken together, European countries are a lot less dependent on China for their imports than the US or Japan because they trade significant amounts between themselves—as would US states or Chinese provinces. However, looking at the EU as a whole and considering trade with non-EU partners, we see that the EU’s dependence on China for imports has increased over the past five years, rising from 22% in 2017 to a peak of near 27% in 2022, and then leveling off to 25% in 2023. In 2019, EU import reliance on China overtook that of the US—as China imports came under broad US tariffs—and has since become gradually closer to levels seen in Japan or South Korea, two economies highly intertwined with neighboring China.

OECD Trade in Value Added (TiVA) data shows a similar trend (Figure 3). The EU’s dependence on Chinese value-added for final demand increased from 13.6% in 2017 to 17.3% in 2020, quickly approaching US levels. The US, in contrast, saw its reliance on Chinese value-added remain roughly stable during the 2015-2020 period. By 2020, Japan and South Korea still showed a much stronger reliance on Chinese value-added than both the EU and the US, but South Korea saw the fastest increase (+5.4pp).

Finally, China’s share of the EU’s outward manufacturing FDI stocks rose by 2pp from 2017 to 2021, albeit from a relatively low base of 4% (Figure 4). EU statistical delays obscure the picture somewhat, but more up-to-date Rhodium Group data suggest that EU manufacturing FDI has continued to flow into China since 2021, with a record high in EU greenfield FDI registered in Q2 2024. Meanwhile, over the past several years, China’s share of manufacturing FDI stocks has declined slowly for the US (-0.2pp) and fast for Japan (-1.3pp).

In short, the EU has seen China’s share of its imports, value-add, and investment increase over the past six years, in contrast to the US and Japan, which have decreased their China exposure on most or all fronts. Of course, aggregate import reliance does not equal critical input dependency—arguably the more substantial type of exposure—but it shows how Europe has been at odds with a broader trend in Japan and especially in the US.

Recent analysis by the Peterson Institute for International Economics reinforces this view, showing that while US sourcing of manufactured goods has substantially diversified away from China over the past five years, EU manufacturing imports have only become more concentrated in the aggregate—a pattern that holds for both low- and high-tech products. A deeper historical analysis by MERICS, focusing on critical EU import dependencies on China, also emphasizes the EU’s dramatically increased exposure to Chinese imports over the past 20 years, particularly in electronics. A separate Oxford Economics study acknowledges that the US and Japan have lowered their share of intermediate goods imports from China while the dependence of European economies has notably increased.

Explaining the differences

These findings beg the question: given that the EU, the US, and Japan are all pursuing efforts to reduce their economic dependencies and diversify their trade patterns, especially from China, what explains the EU’s increasing rather than decreasing trade, value-add, and investment exposure to China in recent years?

A China-powered green transition

A first way to explain this gap is to identify the product categories where the EU’s reliance on China has increased the most since 2017, the year before the US imposed its first round of Trump tariffs on China (Figure 5).

Batteries and electric vehicles (EVs) contributed over a third of the increase in China’s share of EU imports, reflecting China’s growing competitiveness in both fields and increasing dominance of the global EV supply chain. In fact, China’s share of battery imports increased across the EU, US, and Japan (Figure 6A), but the value increase in Europe was much greater (Figure 6B). The same is true of solar cells. Both the US and the EU registered increases in the absolute and relative value of China-origin imports, but for the EU, this happened on a completely different scale (Figure 7A and 7B).

The fact that Europe was an early mover in rolling out policies to support the green transition probably explains some of this disconnect. In batteries, the EU lacked credible domestic competitors (unlike Japan or South Korea) or an industrial policy that attracted such producers onshore (as in the US). More broadly, this reflects Europe’s greater openness to Chinese clean tech imports over the period. By contrast, tariffs and provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) made it harder and/or costlier for Chinese clean tech manufacturers to export to the US.

An energy crisis

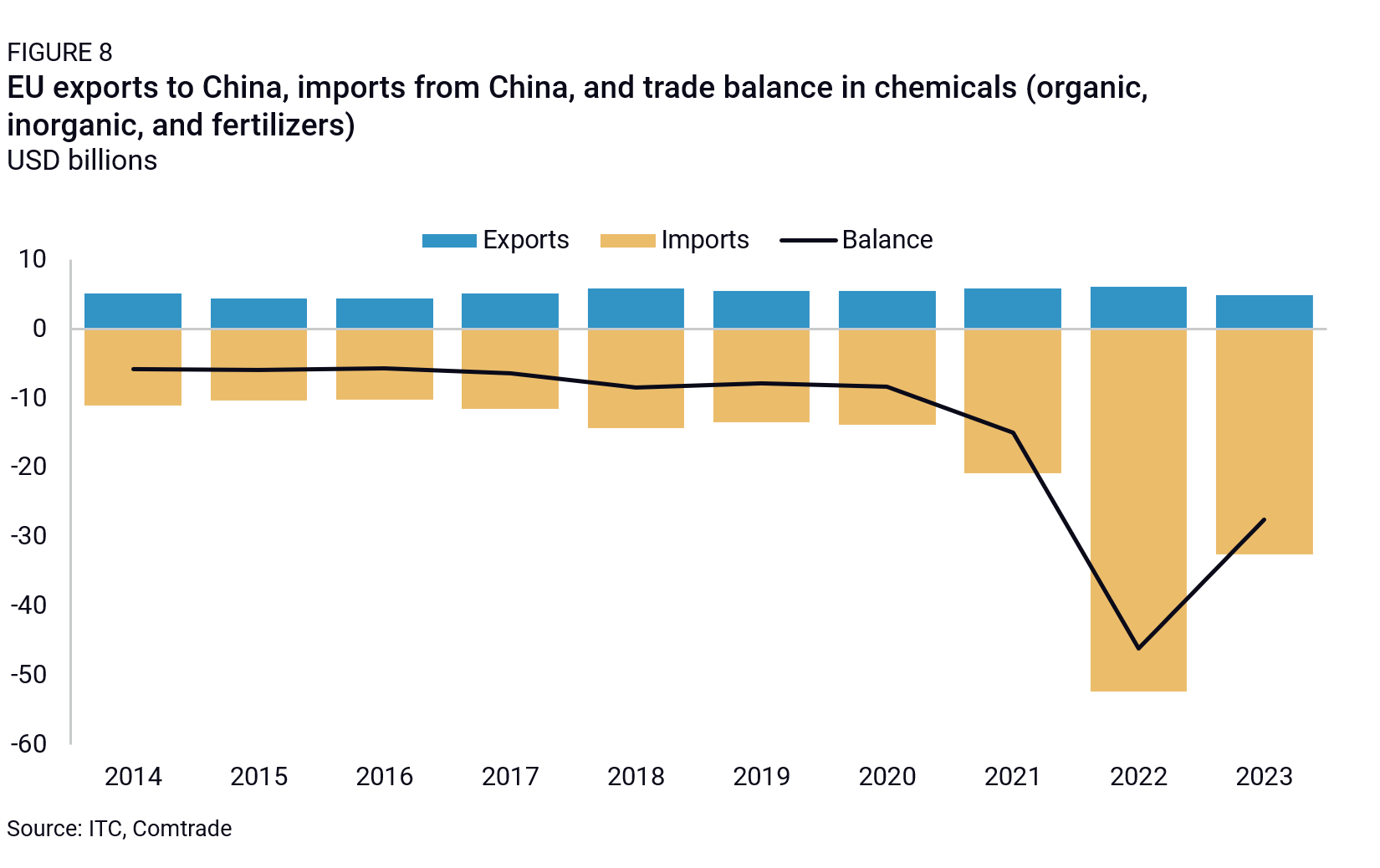

Another explanation for Europe’s growing entanglement with China is the energy crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In recent years, China’s share of EU imports increased quickly and significantly in chemicals—especially organic compounds used in pharmaceuticals—and fuels such as jet fuel and kerosene. Rising energy costs in Europe made importing these chemicals from China—instead of producing them at home—much more attractive. At the same time, rapid production capacity growth in China pushed down Chinese chemicals prices and facilitated export market share gains. Together, these two factors worsened the EU’s trade deficit with China, with key EU chemicals imports more than doubling from 2020 to 2023 (Figure 8). The shift is already triggering EU reactions. Over the past year, Brussels has opened a series of trade defense cases against Chinese exports of chemicals used in food products, cosmetics, and cleaning products, all on the back of industry complaints.

No tariff shock

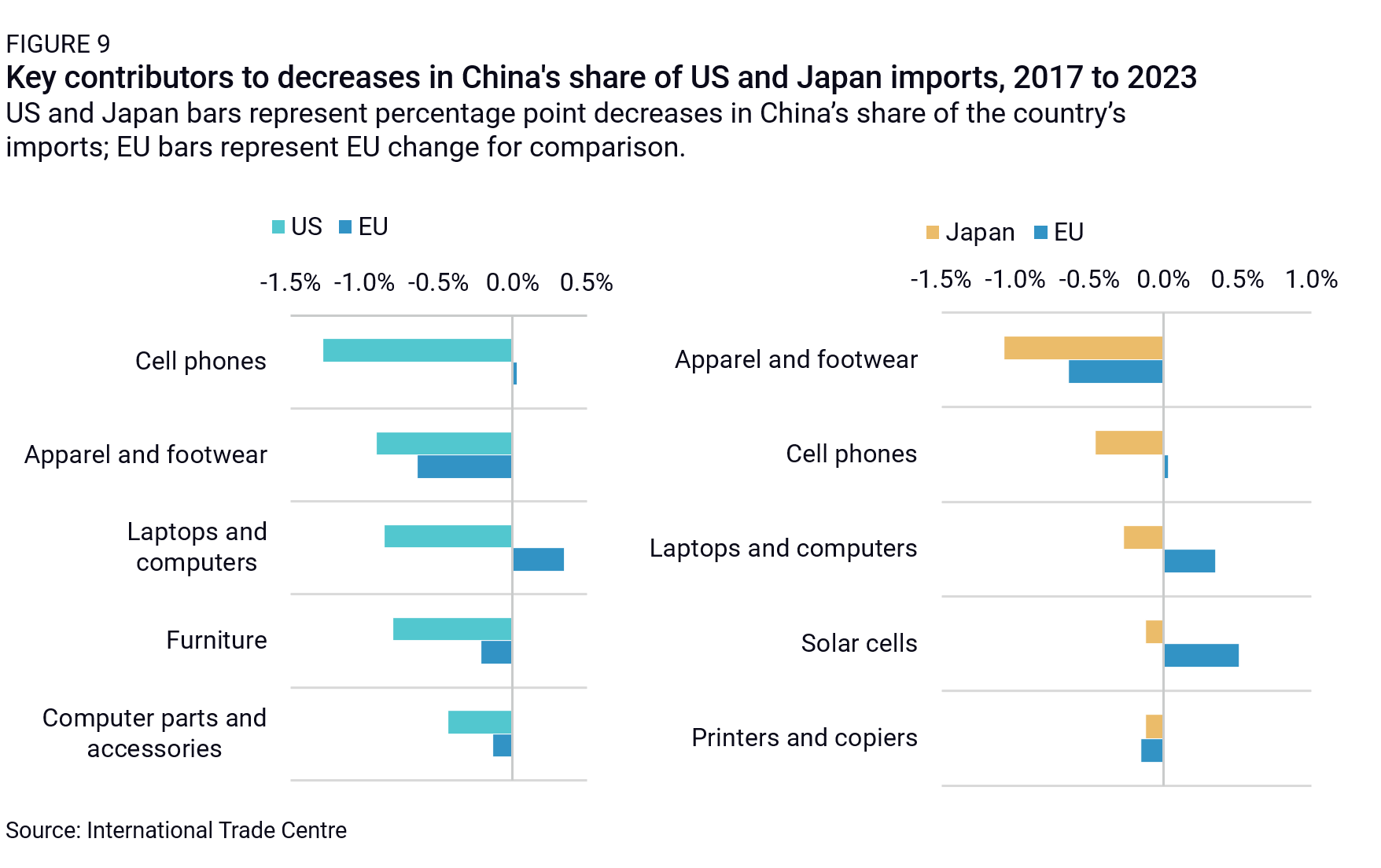

Another way to look at the question is to explore which areas saw significant diversification from the US and Japan but not from the EU (Figure 9). Some of the largest contributors to US and Japanese diversification are labor-intensive, low-value-added sectors such as apparel, footwear, and furniture. In these categories, China’s high global export share began a gradual, structural decline even before the trade war, as it started undergoing a process of “graduation” to higher-tech activities. Although the EU has shifted its sourcing somewhat—to many of the same markets as the US and Japan, including Vietnam and Bangladesh—it has not done so nearly as quickly. The US and Japan have also quickly diversified their consumer electronics imports since 2017. Yet, here again, China’s share of EU imports has either hardly budged (computer parts, cell phones) or increased (laptops, solar cells).

It is worth noting that these sectors are often perceived as less strategic than others, like green tech or specialty chemicals. It is unclear that the EU is even seeking to de-risk from China in these areas. Yet they did contribute to the US and Japan’s import diversification over the past half-decade or so, and hence, they explain part of the gap with Europe.

Policy choices likely explain much of the difference. Starting in 2018, US tariffs on a range of consumer goods imports from China, including some textiles, furniture, and consumer electronics, have redirected production and assembly from China to third countries like Mexico, Vietnam, and Bangladesh. Japan’s subsidy schemes, strong political signaling to domestic firms to diversify production and sourcing away from China, and greater historical footprint in Southeast Asia might have impacted diversification progress, too.

Re-shoring vs. near-shoring

Focusing on trade, lastly, underestimates the fact that China gained important ground while Europe also started producing more domestically. In fact, the jump in China’s share of EU imports is much greater for extra-EU imports (+3pp) than imports including intra-EU trade (just +1pp). This difference indicates that EU member states have quickly picked up market share from non-EU importers. US trade diversification happened largely thanks to external players, including Mexico, Vietnam, and Taiwan. But in sectors like semiconductors, massive new investments in the US also suggest diversification is or will be happening through a ramp-up of local production.

In Europe, some degree of diversification is similarly happening on the back of production increases in select EU member states—including and especially Central and Eastern European economies, who share some of the manufacturing appeal of ASEAN or Mexico. In the battery sector, for example, Poland, Hungary, and Czechia have emerged as significant players, increasing their share of total EU battery imports from 7% in 2017 to 35% in 2023. While this does not negate the fact that the EU’s import dependency on China increased over the past five years, it indicates greater “friendshoring” activity than topline trade numbers indicate.

EU policies: More bark than bite

Could structural differences between the US and EU economies, finally, help explain some of the observed differences? What if Europe were intrinsically more dependent on global trade than the US? Or what if the US was significantly more service-oriented than Europe? A closer look shows that both economies have, instead, similar levels of manufacturing output as a share of GDP, a comparable degree of reliance on intermediate input imports in their manufacturing sectors, and a similar level of imports as a share of their overall economy. Both economies are major markets for (and importers of) autos, batteries, solar PV, and chemicals.

This leads us to the conclusion that the variation in results is due to policy differences between the EU and the US between 2017 and 2023. On the surface, both EU and US policymakers have adopted diversification as an overarching policy principle—especially as the COVID pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine underlined the risks of excessively concentrated supply chains or supply sources. Both EU and US officials have raised specific concerns over excessive exposure to Chinese imports, especially to certain China-made critical inputs. Yet policy reactions have been very different. For one, the US took action several years before the EU. The first major wave of US tariffs against China was rolled out by the Trump administration in 2018, years before the EU started using its defensive toolbox in full or defining “de-risking” as a policy objective. Also, US policies, including export controls, industrial policy support, and ICTS measures, have involved a much more robust set of carrots and sticks than their European equivalents (Table 1).

Trump-era tariffs are an obvious example. They brought the effective tariff rate on Chinese imports to the US to around 11-12% and affected about two-thirds of Chinese exports to the US before a series of exemptions were introduced. In contrast, the EU’s largest case to date, on China-made EVs, covers about 2% of China’s exports to the EU.

Consider major state support programs. Both the EU and the US have launched major sectoral and decarbonization support schemes in recent years. Yet US initiatives have come with stringent, binding conditions and guardrails meant to encourage diversification of related supply chains away from China. In contrast, the EU’s main regulatory framework for critical raw materials and cleantech diversification, the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) and Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA) offer non-binding targets for EU’s manufacturing of clean technologies and extraction, processing, refining, and recycling of raw materials.

Finally, in certain sectors, the US is simply choosing to ban some Chinese goods and technologies in ways that will fully reshape US-bound supply chains—as is the case with the latest ICTS rules on Chinese and Russian connected vehicles.

This is in addition to an intense and bipartisan US regulatory agenda on China and a highly China-skeptical political environment, both of which are sending clear and credible signals to US companies that they need to diversify now or face costly consequences. The draft BIOSECURE Act is a potent example. This bill would prohibit US federal agencies from procuring or obtaining biotechnology equipment or services from certain “biotechnology companies of concern” (currently, five Chinese biotech firms) or contracting with any entity that uses such equipment in the performance of federal contracts. While the act has yet to be passed by Congress and signed into law, it has already created a powerful enough signal that some US companies are reconsidering their ties to Chinese biotech firms. In October 2024, Wuxi AppTec, one of the listed firms, was reportedly considering the sale of some US laboratories and manufacturing plants in response to growing regulatory pressures.

Japan presents another successful example of policy-driven diversification, focused mainly on encouraging companies to de-risk through positive incentives. Like the EU, Japan’s de-risking programs do not explicitly target China, but many Japanese firms have dubbed these government incentives as a “China exit subsidy.” Programs such as the Program for Strengthening Supply Chains and the Program for Promoting Investment in Japan to Strengthen Supply Chains provided substantial financial support to firms reshoring their operations to Japan or relocating production to other Southeast Asian countries. Japan’s subsidies to attract investment in key sectors such as semiconductors and electric vehicles also far exceed EU funding. Overall, Japan is expected to disburse about $65 billion in subsidies to support the semiconductor industry by 2030, compared to $57 billion in the US and only about $9 billion in the EU.2

Outlook: What about the next five years?

In 2023, China’s share of EU imports (excluding oil and gas) was down almost two percentage points from its 2022 peak. The question is whether this signals a longer-term shift or just a short-term correction after particularly high Chinese export prices in 2022.

In the short run, we think the EU’s dependency on Chinese imports is likely to deepen further. China’s economic weakness will perpetuate the gap between consumption and production and compound the urge to grow exports as a lever of growth. As a major global market, the EU will be on the receiving end of these flows. Trump’s decision to impose further tariffs on China will likely accentuate the trend. The first iteration of “Trump tariffs” had a significant impact on US-China trade flows and global supply chains more broadly. On the 2024 campaign trail, Trump promised to slap 60% tariffs on Chinese exports to the US. Whether or not these are implemented in full and at these levels, additional US tariffs will end up redirecting some Chinese exports to Europe. China’s responses, which will likely involve significant RMB depreciation, will further amplify the trend and significantly increase the cost of diversifying manufacturing or sourcing to other emerging markets.

Because Brussels is already concerned about Chinese overcapacity and a potential influx of low-price Chinese products, it is unlikely to sit idle, of course. We would expect the Commission to launch its own series of trade defense cases. These could involve more drastic measures like safeguards, already used to shelter Europe from the effects of US tariffs in 2018. Yet because Brussels is still intent on using WTO-compliant tools, at least in the short run, and because these necessitate a sectoral focus, EU officials will need to prioritize their defensive efforts. Primacy will likely be given to large value-add and job contributors, like chemicals, machinery, or select clean tech equipment—in addition to EVs, which are already in focus. Sectors where the EU does not have as much of a local industrial base—such as textiles, furniture, and electronics—will likely remain open and see a rise in Chinese imports. Because exporting hubs like Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Thailand will redirect production capacity to serve the US, Europe’s needs might end up being addressed, even more so than in the past, through China-based capacity.

In the long run, Europe might shift back to diversification. Product categories that have seen major upticks in Chinese import exposure over the past five years could progressively become the target of more defensive action from Brussels. Given the EU’s dependency on China for solar PV supply, it is unlikely that the Commission would launch a major trade defense case for solar. Brussels, however, already launched an ex-officio FSR case against Chinese firms active in Europe’s wind sector. If European battery champions continue to face financial difficulties, the Commission could consider additional action on battery imports—if just to foster greater investment on the ground in Europe. These actions, and possibly more, would constrain Chinese firms’ EU market share, including through exports.

Beyond trade and subsidies cases, Europe might also start using more stringent regulations and public procurement criteria to force a diversification of vendors away from China. Lithuania and the Netherlands have already introduced laws that bar certain Chinese technologies and products in wind and solar projects on cybersecurity grounds. The NZIA and CRMA allow resilience criteria in public auctions, which could de facto limit Chinese supplier access to a range of publicly procured contracts in Europe. The EU is currently revising its public subsidies rule to similar effect. Finally, certain member states like France are introducing their own standards-based criteria for access to certain public funding schemes—namely environmental standards-based tax credits for EV purchases—in ways that make Chinese imports less competitive.

In short, measures from member states are likely to further restrict Chinese firms’ access to the EU market. These moves will probably persist even as member states seek to hedge against Trump through greater China outreach. They could even be fast-tracked if further evidence emerges of the cyber and resilience risks attached to using Chinese goods, technologies, or systems, such as evidence of Chinese firms sending sensitive data back to China or Beijing, significantly restricting access to certain critical inputs or raw materials.

Positive inducements to diversify European manufacturing and sourcing at scale have been harder to deploy for the EU, but they are not out of the question. European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen’s political guidelines include pledges for pan-EU funding for key areas of European competitiveness, and certain member states like France have long argued for more forceful financial support to European industry and innovation. Germany and a few other member states will prove major obstacles, but increasing pressures from the US and China could drive a step change in approach.

Finally, US regulatory bans on certain Chinese goods and inputs, like the new ICTS rule (see October 8, “Car Trouble”), will create incentives for European firms to diversify their supply chains away from China faster than they have so far.

In that context, EU diversification could pick up on the back of US, Japanese, and Chinese diversification. As investment continues to flow to ASEAN and other “alt China” destinations, non-China production capacity will expand in ways that will make it much easier for European firms to procure or manufacture outside of China in the long run.

No comments:

Post a Comment